|

I did what's called a "Practice Period" at Tassajara last fall -- which means that I lived at a monastery in the Ventana Wilderness, 12 miles inland from Big Sur, for three months with forty-five other monks. When I left the Practice Period last December, it was with the idea that I would return as soon as possible. At first I thought I'd straighten out my worldly affairs and be back in April in time to work there over the summer and "earn" the tuition for my next two practice periods, but life intervened with its own ideas about the timing of this event and I floundered around for an extra four months, getting further in debt and adding extra layers of complication to my life. So now in late July I’m finishing up real estate stuff and looking around my apartment trying to figure out where to start in compressing fifty-eight years of living into a monk's cell. I first heard about zen in 1964. I was living at Bush and Octavia, across the street from the original Zen Center where Suzuki-roshi taught. I heard about it, and chose not to cross the street to meet the guy. But that decision was understandable: my informant told me that zen was about "ending desires." It's not. I'd say today that zen is about learning to live with desires. I do regret never having met Suzuki-roshi. My next chance was in 1978. I was coming to the end of 20 years of hard drinking; in my desperation, I started going to the Saturday morning talk at City Center, and was taken to Green Gulch on a Sunday morning to hear Baker-roshi give the talk there. I picked up a copy of Zen Mind Beginners Mind, the collection of talks by Suzuki-roshi. When I got home, I flipped through it. What a disappointment. All he talked about was zazen (meditation). I wanted the answer, and I wanted it immediately. I put the book down for about ten years. In the meantime, I sobered up. The twelve steps specifically mention meditation, and on my ninth sobriety anniversary in 1988, I sought out someone who could teach me that skill. I found zen much too intimidating to embrace easily; naturally, zen is the flavor of Buddhism I ended up practicing. I took my lay vows in 1996, and began sitting daily at City Center in January of 1999. I asked the Abbess, Blanche Hartman, to accept me as a student some time in the summer of 2000 and went to Tassajara with her in the fall of that year. Here are my notes, written 12/27/00, right after I came out of Tassajara, which explain more about the structure of a practice period: Zen is experiential. All the words in the world are of little consequence compared to the power of sitting still and silent for hours on end staring at a wall. But I still want to try to convey something of my first practice period at Tassajara before the memories are too faded and tattered by the attempt to tell them to my friends as I re-enter the world.

Zen is all about the forms, and Tassajara is the high temple of zen in America. I've been practicing intensively at Zen Center's building in San Francisco for a couple of years, and probably thought I was pretty slick, but at Tassajara I was a beginner again. I rebelled against the Japanese-ness of it early on, and was soothed by Blanche's reminder that the forms are there to help us wake up in each moment, and not just a bunch of meaningless rules. So I stopped fighting and began to pay close attention to the way I walked, sat, held my hands, and ate for 90 days. The things that we take for granted -- sleep, privacy, and heat, for instance -- were withdrawn. Zen itself is designed to throw us off balance, and the practice period schedule is designed to keep us ragged. It sure worked. In an average day we meditated for two hours and then bowed and chanted for another 30 minutes before we even saw a tiny speck of food. We did 27 full bows (from standing with our hands in prayer position to on the knees with the forehead touching the floor) in an average day and sat six periods of zazen ranging from 40 minutes to an hour. Meals were served in the zendo as we sat cross-legged on our zafus, the portions were small and the time in which to eat them was rushed. We were in silence from wakeup until after lunch, and even then the chances to talk were limited. The schedule was on a five day cycle, with three days of monastic practice, one day of work, and one day with free time between breakfast and dinner. It seemed that the bells ringing to tell me I had to be somewhere never ended. We were in robes from the start of the day until after lunch. Sometimes I'd use a ten minute break to lie down on my bed. The robes are so complex to get in and out of that I'd leave them on while I laid down straight on my back with my arms at my sides, just like a corpse, trying to satisfy both my need for rest and my need for a tidy appearance. My hair was a couple of inches long when I arrived, and not long after that I buzzed it down to one inch; there was no time to attend to even two inches of hair. Laundry was done by hand in an outdoor shed and hung on lines to dry. The laundry room was one of the great gathering places on days off. The diet was vegetarian and also wheat-free and dairy-free. Each meal had either tofu or beans for protein. There's a "back door" area of the kitchen where there's always a big bowl of fruit and, after lunch, bread and peanut butter and various jams and jellies. I ate at least one peanut butter sandwich every day. During sesshin (more intensive periods of meditation) the bread was withdrawn, and I saw students smearing peanut butter directly on bananas and wolfing it down. The food was good, but monotonous. It began to feel that there were five basic menus that we kept rotating through.

After the initial shock to my system, both physical and emotional, I settled in happily at Tassajara. My 57-year-old body became leaner and stronger, and my resistance to the relentless nature of the schedule subsided. I found space and time to explore the teachings, and moved into the opportunity which presented itself to experience them directly. I formed some very precious one-on-one relationships. Gratitude arose. There was freedom in surrendering to the restrictions imposed on us at Tassajara, and an incredible luxury in having all of my basic needs met. Now, seven months later, as I prepare to live and work in City Center for the seven weeks before I return to Tassajara, having quit my job, given away my cat, and given up my apartment and my car, I have been freaking out about the one-wayness of this decision. It feels as if I'm going down the rabbit's hole and there will be no way out. This is mostly economic, but I suppose there's an emotional element too. It's really hard for people to leave Zen Center, and I'm already so old that I'm less likely to be able to make that change in the five or so years that I imagine my training will take. I couldn’t make this change without the help of my friends who’ve already done it. Last Saturday I was helping prepare for a ceremony at Page Street, and was working with a woman who's been living there for about a year. While we were working together, she said that she was always glad when I was around the building. I said I was going to be moving in, and she literally clapped her hands with glee. So we talked about being a resident. I said something to her about my feeling that moving in was moving down a one way street, and she answered "oh no, moving in is moving in to everything." That helped. One of my closest friends is a Tibetan nun. We spoke on the phone last week, and she also reminded me that I was going to something, not from something. Renunciation frees us up for concentrating on things other than getting and spending, and it's only when I'm on the outside looking in that it feels like nothing but an opportunity for a new kind of suffering. The kind of renunciation I know about is living simply. My little cell last fall was about seven feet square, and the closet had enough room for my robes and about four shirts and sweaters. There was plenty of anxiety around which shirts and sweaters they should be -- one of the first things I did after I arrived was get on the phone and mail order some stuff -- but once that was settled, it was very restful to not have to face a wall of clothes and pull something together every morning. More important was the renunciation of silence and following the schedule completely. A lot of energy gets lost in picking and choosing; having a whole bunch of decisions already made freed up my energy to explore "the great matter." Which is, after all, the point.

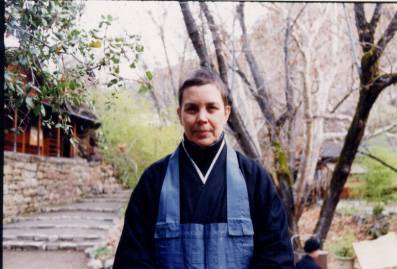

©2001 by Judy Bunce  Judy Bunce is a zen monk currently living at Tassajara Zen

Mountain Center, the training monastery of San Francisco Zen Center.

Judy Bunce is a zen monk currently living at Tassajara Zen

Mountain Center, the training monastery of San Francisco Zen Center.

All photos © Judy Bunce

|

| Home | Favorites | Links | Guidelines | About Us |

|

|

Tassajara is in the Ventana Wilderness south of Carmel Valley, reached by driving for an hour over a one lane dirt road that goes up a mountain and then descends into a deep valley. The whole place is about one mile long. At the mid-point, where the road comes in, there are the three main buildings: the zendo, the dining room, and the kitchen. To the east, across a twenty foot wood bridge, is a clump of small cabins, the large lower garden, and a swimming pool. To the west, there are some stone buildings including the office, some posher guest rooms, and the communal baths. Tassajara creek runs through it, constantly making its presence felt through the noise of rushing water. Tassajara is completely off the grid, and is lit primarily by kerosene lamps, although a few of the buildings now have electricity. Long before Zen Center bought the property, it was a rustic resort. We now are open to paying guests from May to September, and become a full-blown monastery for two three-month practice periods a year.

Tassajara is in the Ventana Wilderness south of Carmel Valley, reached by driving for an hour over a one lane dirt road that goes up a mountain and then descends into a deep valley. The whole place is about one mile long. At the mid-point, where the road comes in, there are the three main buildings: the zendo, the dining room, and the kitchen. To the east, across a twenty foot wood bridge, is a clump of small cabins, the large lower garden, and a swimming pool. To the west, there are some stone buildings including the office, some posher guest rooms, and the communal baths. Tassajara creek runs through it, constantly making its presence felt through the noise of rushing water. Tassajara is completely off the grid, and is lit primarily by kerosene lamps, although a few of the buildings now have electricity. Long before Zen Center bought the property, it was a rustic resort. We now are open to paying guests from May to September, and become a full-blown monastery for two three-month practice periods a year.  Of the forty-five people in this practice period, twenty-two were there for the first time – Tangaryo students, we were called. We remained in a special category and rotated through several special jobs -- lighting and extinguishing the thirty-some kerosene lamps that lit the paths, ringing some bells, and serving meals. We were pretty evenly divided between men and women, and probably also pretty evenly divided between people below thirty and those above fifty. We became the student body in a very deep and profound way. We worked for two hours a day during a regular monastic schedule -- we cooked, dug ditches, harvested persimmons, cleaned rooms for guests, and cleaned the zendo. I generally cooked. In the kitchen, we always worked in silence on assignments like rough chopping three gallons of onions or pressing and slicing fifteen blocks of tofu. We had four sesshins (periods of more intense meditation) during our time there, and I spent one of those working in the kitchen.

Of the forty-five people in this practice period, twenty-two were there for the first time – Tangaryo students, we were called. We remained in a special category and rotated through several special jobs -- lighting and extinguishing the thirty-some kerosene lamps that lit the paths, ringing some bells, and serving meals. We were pretty evenly divided between men and women, and probably also pretty evenly divided between people below thirty and those above fifty. We became the student body in a very deep and profound way. We worked for two hours a day during a regular monastic schedule -- we cooked, dug ditches, harvested persimmons, cleaned rooms for guests, and cleaned the zendo. I generally cooked. In the kitchen, we always worked in silence on assignments like rough chopping three gallons of onions or pressing and slicing fifteen blocks of tofu. We had four sesshins (periods of more intense meditation) during our time there, and I spent one of those working in the kitchen.