Entering the Monastery:

An Ongoing Journal

by Judy Bunce

September 26, 2001

It's the morning of the third day of the fall practice period at

Tassajara. For me, it's a day off. I'm on kitchen crew for this three

month practice period, which is something that everyone who stays at

Tassajara long-term has to do sooner or later. I'm sitting on my bed with

two kerosene lamps burning and my laptop running on its battery. What a

life.

I got a great room assignment. It's one of the pricier rooms during the

guest season. It's in the yurt, a wooden structure way down by the pool.

It's insulated, and each of the three rooms has a wood stove, so the

prospect of not freezing over the winter is good. My room is

round, probably fifteen feet in circumference, with lots of windows, and even a

skylight that opens. It looks onto the hillside. It has two twin beds,

which I've pushed together to make one huge luxurious bed, but I've also

told a couple of friends that if they get too cold during the winter they

can come and stay with me, so the bed may be split again.

The strangest thing about being here is that it's as if I never left. Most of

the people who I started with last year are still here, and I seem to have

been inserted back into my "class," as if I'd been here the whole time. I

know that the seven months I was away happened, and my heart and mind turn

toward the people who I was connected to during that time. I remember

working and living in the city, I remember that the country's in a

terrible crisis, and roll the words "Osama bin Laden" around my mind, but

only this seems at all real.

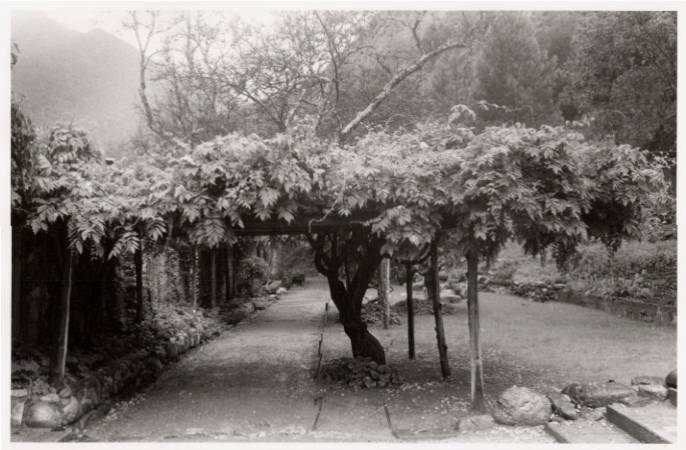

Tassajara is a tiny bunch of buildings tucked into the middle of the

Ventana wilderness, and it could be that the animals think they got here

first. Last night when we were sitting in the zendo, one was gnawing away

on one side and another was flinging itself against the screens on the

other. They behave that way outside my room, too, usually around 1 a.m..

The mouse problem is so severe this year that I heard

about it when I was still at City Center. A raccoon tried to open my

screen door and waltz on in while I was sitting on my bed the first night.

I laid in my bed last night listening to the animal noises, feeling the

fear that they waken in me. I felt like Eve, all soft and unprotected

against creatures who were armed with sharp teeth and long claws.

Now I see a little bat flying around above the deck, snacking on some

tasty bugs before it calls it a night. The bluejays who decided to

winter here are screaming in the distance. The crickets are chirping, and

if the deer haven't worked the area recently they'll be here soon. There

was a great thunderstorm the first night here. I think that's pretty

unusual for September. It woke me, and I laid in my bed looking at the

lightning flash in my skylight. I wasn't the only one who wondered

whether this was a sign of what the practice period would be like.

October 16, 2001

Not long after arriving here, struggling with the physical demands of the

kitchen schedule and my feelings about not being in the zendo with the

Abbess, I saw the real price of renunciation: it's the people. Leaving

behind the car and the television and even the cat is nothing compared to

the people. I take naps on my breaks and have dreams that I'm with people

on the outside and we're saying goodbye and we're hugging and kissing and

tears are falling like rain. I had forgotten how isolated we are here.

Yes, there's a telephone, and yes, we get mail, but the phone is moody and

the mail infrequent. And what is there, really, to say to anyone on the

outside, anyone who's not a part of this one body with forty-five hearts living

this most peculiar life?

There's all of this, the beauty of the place, the amazement of dealing

with nature up close, the loveliness of watching the kitchen crew become a

unit and the larger group settle in -- and there's the big question on many

of our minds of what it is we're doing here and whether it's reasonable to

live like this when the outside world is going mad. This is no vacation,

but it is merely selfish if we're just forty-five people who have turned our backs

on the world to try to heal our own wounds, calm our own hearts and minds,

find a way of living that makes sense to us as individuals. If we truly

believe that we're all one, though, then it follows that there is a

benefit to these forty-five parts of the whole working on growing in wisdom and

compassion, that when one grows in understanding the whole world does. Or

I hope there is.

November 7, 2001

It's starting to get cold. I got a new wool robe and flannel kimono, and

am now wearing them both every morning with silk long underwear. I think

it's time to start adding the thermofleece vest under the robe. We start

the day by sitting for ninety minutes, and it's during that cold time before

the dawn. When we left the zendo after breakfast this morning, after the

sun had risen, it was 35 degrees, so it must have been down near freezing during

zazen.

I'm using the wood-burning stove in my room every day now. My windows

face east but there's a hillside about twenty-five feet away, so I get no direct sun at

all, and it stays cold. When I get home from work after lunch, I light one

log and then let it smolder for the rest of the afternoon. It works well

to keep the chill off. But I think the mice like it too. I have finally

figured out that they're the cause of the noise near the head of my bed:

it's mice in the walls. I thought it was raccoons trying to claw their

way through the walls and eat me alive, but it's just little mice.

The raccoons are just awful. They know all of our bells, and they respond

too cleverly. If I don't keep the kitchen doors bolted when I'm there

alone on the days I cook breakfast, they try to come in and have shredded-wheat parties. There was a woman here from Florida for the Soto Shu

sesshin a couple of weeks ago who finally told me, after much hemming and

hawing and looking over her shoulder, that someone had opened her door at

3 a.m. and then slammed it shut when she called out. She said "I heard

footsteps, but when I looked out no one was there." I was sorry to tell

her that it was raccoons and not ghosts. As far as I know, the ghosts

confine themselves to the zendo.

There's an animal call that we hear before dawn that's just beautiful,

sort of chirpy and fluttery and sweet. I thought it was foxes -- and told

several new people that it was -- but someone said it was raccoons. If so,

at least there's one good thing about them.

One of my flip-flops was stolen from outside my door, and an oldtimer

guessed it was the foxes. When they get hungry they come down from the

hills and steal shoes for the leather. The flipflop is rubber, and

whoever stole it discovered their error and spit it out -- ptui! -- behind a

fence about fifteen feet away.

It's a pretty funny bunch of animals trying to find a way to coexist here

in the Tassajara valley.

November 23, 2001

November 23, 2001

The five day silent sesshin is over. Volunteers traditionally move into

the kitchen for this so that the crew can sit it. In addition to moving

from the kitchen to the zendo, I was asked to serve as the Abbess's Anja

(personal assistant) for the week.

The Anja job meant knocking on Blanche's door twenty minutes before each zendo

event, and spending about the same amount of time with her when we left

the zendo. I woke her, made her bed, brought her hot water, kept her

supplied with firewood, built her fires, and cleaned her cabin. After

meals I'd slip out the back door of the zendo so I could be in her cabin

when she arrived; I'd stand behind her and receive her okesa when she

removed it, and fold it and put it away for her. During work period I did

repairs on it.

This schedule meant that I got six hours of sleep a night and three twenty-five

minute breaks a day. While everyone else was resting, I was taking care

of the Abbess. We had a closing ceremony last night where I told the

group that the job's hours were terrible, but the pay was great.

I love abandoning the clock and going by the bells, but I couldn't do that

this time, since my schedule was different from the group's. One morning

when I heard the wakeup bell ring I said "Oh shit," hopped out of bed, and

sprinted for the bathroom. If the wakeup bell was already ringing, I was

late. I poured my thermos of hot water into my basin to wash myself -- and

then saw that it was only 12:30. I think the creek was playing a joke on

me. I told this story at lunch today, and several other people agreed

that they hear wakeup bells and densho bells in the creek. Too bad I'd

already poured out my hot water, though -- it was stone cold when I got up

to my alarm at 3:30.

November 26, 2001

The day after sesshin ended, I was summoned to dokusan with the Abbess.

For the third time, we talked about my ordaining. I initiated the topic,

and she very matter-of-factly agreed. The next step is to talk to the

other Abbotts and get their approval, and then (if they do indeed approve)

I can begin sewing my okesa, the large toga-like garment which priests

wear on top of their robes. The whole process usually takes about a year.

We talked about what it means to be a priest and she, as usual, quoted

Suzuki roshi, saying he didn't know. We've touched on the celibacy

requirement in previous conversations --- learning to be a priest takes total

attention and energy, and people who meet someone and fall in love are

required to put their priest training aside for a year while they work on

the new relationship. The entire period of close training is about five

years. As far as I know, the other requirements are to be kind and try to

see the Buddha in everyone. She asked me to begin acting like a priest

immediately.

My mind was blown. This is what I came here for, but it seems too

daunting to undertake. On the one hand, I feel entirely inadequate to the

task. On the other hand, and that hand is currently the stronger one, it

seems like something I must do. There's a wonderful young Italian priest

here right now who asked whether I was going to ordain, and when I said

yes, he was very pleased. I indicated that I was nervous about it and he

said that ordaining was like riding in a plane through turbulence and then

rising above the clouds into the clear sky. That's useful information.

Blanche's regular Anja became very ill, so I helped out over the last

few days while I was working in the kitchen too. I did her laundry two

days ago, and the weather's been so heavy and the air so moist that it

never dried out. That's why right now I have Blanche's underwear hanging

all over my room and am burning logs like mad to keep the temperature up

so it can dry.

December 4, 2001

Last August I rented my apartment furnished, and about two weeks ago got

a message from my tenant saying he'd be leaving at the end of December. I

put my personal stuff in boxes in my cousin's garage and about a week ago

got a letter from her saying she was selling her house. I heard about a

self-storage place in San Francisco and learned that I could get a good

rate from them for long-term storage. I found my mover, and he's available

the day I need him. I even arranged to have my white couch cleaned before

I put it away. I have no desire to live in San Francisco right now, or to

live anywhere but at a Zen Center place. Still, this afternoon, when I

got mail from my landlord confirming receipt of my thirty day notice, I found

that I felt sad. It's like getting a divorce from someone who you don't

much like: relief that it's over is temporarily outweighed by sorrow over

such a good idea turning out so badly.

Last night I woke up to find that I was lying in the center of a circle of

moonlight, flooding through my round skylight. When I was walking up to

the kitchen to start breakfast while everyone else was still sleeping, I

was surprised to see that the moon wasn't even full. I've wakened other

nights to see it shining other places in my room, but this is the first

time it's been on me. I wonder if it does that every night. I suppose

so.

December 9, 2001

Myo Lahey, the Tanto (practice leader) down here, has begun offering brief

dokusan -- five minutes, in and out, and I've taken him up on that offer.

The second time we talked, it was about renunciation being the primary

quality that makes a good priest. He defined renunciation as being free

from attachment to stuff and free from a separate sense of self, and I

said "Who wouldn't want that!"

The leaves have nearly all fallen from the trees, and when I walk back to

my room at the end of the night I can see the stars in the sky.

Yesterday was a work day and one of the crew was out sick, so we were

really kicking it. Toward the end of the morning I was getting something

from the walk-in, and this thought streaked through my head: What's the

difference between doing this and sitting in the zendo? I thought:

Nothing! and laughed and kept on getting lunch ready.

Rohatsu sesshin, the great celebration of Shakyamuni Buddha's

enlightenment, starts tomorrow. The schedule sounds grueling. When it's

over there's one final ceremony, a lot of running around, and we're done.

And after that: we start again.

December 20, 2001

Well, that's it.

One suitcase, two boxes of laundry (because I didn't want the funky

kitchen stuff to contaminate the rest of my dirty clothes), and the rug I

brought down, which turned out to be too fragile for this place, are all

waiting to get loaded on the truck for the ride to the city tomorrow.

My room is both clean and tidy, thermoses and flashlights have been

returned to their rightful owners, and I've even done my Christmas cards.

It's been pouring rain all day.

I worked my last shift in the kitchen yesterday morning. Tomorrow morning

we have zazen and a closing ceremony, and after a bowl of cold cereal we

hop into cars and leave Tassajara. Some of us are leaving for good -- a

few who came for just one practice period, others who've been here for a

while and are now going back to Green Gulch or City Center, and even one

or two who are just getting the hell out of here. A lot of tears were

shed today.

Apparently I'll be staying in the same room for the next practice period,

which is great. I don't yet know what my job will be. Today I couldn't

stand it any longer and asked the director what I'd be doing, and she said

that was usually decided during the first week of the practice period, so I

just have to wait. I am so glad I'm one of the ones who's just leaving for

vacation and will be coming back. Three months is much too short a time

for this thing we do here.

(Continue to Part 3)

©2001 by Judy Bunce

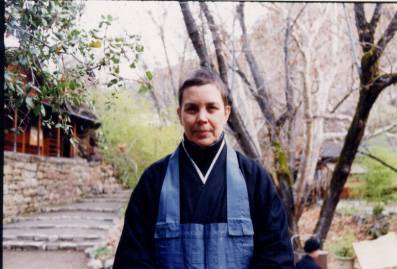

Judy Bunce is a zen monk currently living at Tassajara Zen

Mountain Center, the training monastery of San Francisco Zen Center.

Judy Bunce is a zen monk currently living at Tassajara Zen

Mountain Center, the training monastery of San Francisco Zen Center.

Judy Bunce is a zen monk currently living at Tassajara Zen

Mountain Center, the training monastery of San Francisco Zen Center.

Judy Bunce is a zen monk currently living at Tassajara Zen

Mountain Center, the training monastery of San Francisco Zen Center.