Story From a Quilt

by Margaret Coulson

Australia

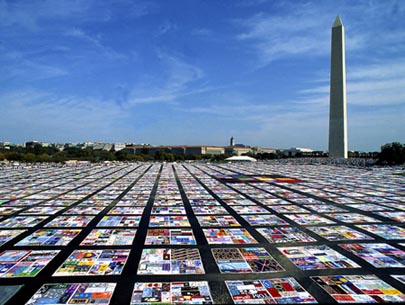

Somewhere in the world there is a quilt, patched together with love and

tears, weaving the stories of lives cut short. Some of the patches are

professional and intricate, hundreds of hours of fine point needlework

telling the tale. Other patches are not so delicate, but equally sewn

together in commemoration by people who care. Somewhere on the quilt,

there

is one patch, amateur in appearance, its parts disconnected, the

stitching

crooked and awkward. The maker of the patch cursed her lack of artistic

talent, the collage of simple images failing to capture the complex

beauty

of her friend. Yet, when seen as part of the quilt, one patch among

many, it

too exudes a story of celebration and pain.

On the top left hand corner there is a bright, yellow sun, the

innocent

type of sun drawn by pre-schoolers with its rays shining down. Beneath

the

sun, the opening bars of "The Old Rugged Cross" are interwoven with

tiny zig

zag patches of blue. The story of how he radiated light. The man and

his

music. The church on the sea.

Alton was fragile as glass, his wiry, copper hair forming an unruly

halo of

curls that seemed somehow too heavy for his slight frame to carry. His

skin

was pale, almost transparent, yet soft as the day he was born. As if in

compensation for his physique, Alton could play Handel so that angels

sang.

The light where we lived back then was harsh and piercing. Specks of

sweat

on his knuckles in the midday heat. Ruddy, rich faces of children whose

parents were successful farmers and doctors and lawyers staring

politely in

resistant silence. These successful farmers and doctors and lawyers had

built a church which overlooked the ocean. A clear glass window with

Jesus

on Galilee had been strategically placed so that He appeared to be

walking

on the water.

Most church musicians accompany the choir, but Alton's melodic playing,

the

voices of the choir, the gentle lull of the ocean were all one, a

single

entity, soaring in exultation towards the heavens. The church has

extensions

now and the pipe organ has been replaced by an electric piano. Salt

breezes

are not kind to musical instruments. Jesus still walks on the ocean but

somehow the building has become colder with age. The bitter sun shines

accusingly at the words of the hymns as they are projected onto a

screen at

the front. I can no longer feel my friend in this place which so

willingly

took his divine music, yet so cruelly discarded him when his body was

spent

and he could no longer play. The rejection was subtle of course. A

refusal

to shake hands. A pointed sermon. Whispers and stares. Throughout it

all,

Jesus still stared from the window with a faint, half-smile. He never

wept.

In the top right hand corner there is a hammer and sickle, with some

bars

from the "Russian National Anthem" beneath. Beside the hammer and

sickle

there is a cage. Prison cell when he was arrested. Trapped by the depth

of

his beliefs. Caged by society because his sexuality did not

conform.

Communists were rare in Australian towns which boasted churches that so

convincingly

depicted Jesus performing miracles. The tiny rooms where Communists met

were

dark and smoky with nervous-looking people who mostly spoke in strange

accents. The piano was always old but Alton would still have been able

to

reach the angels, if only Communists didn't swear atheism as part of

their

creed. The songs however, were always spirited and stirring, offering

hope

for the working classes whose parents couldn't afford to contribute to

church building funds. Alton was buried with only one prized

possession, a

copy of "Das Kapital" I had given him for his twenty-first birthday. It

was

the second copy he'd owned. I'd first given him a copy for his

seventeenth

birthday. It had been destroyed in a flurry of batons and paddy wagons

during an antigovernment street march two days later. Blood on the

walls of

a soundproof, padded cell. Rough hands and furtive nakedness claiming

his

puny body. Even as he rejected the pain, he had been exposed to a

possibility that boys from parochial Australian towns did not know

existed.

Being a student and a Communist is a good combination. It allows you to

feel

self-righteous about egalitarianism because you are forced to be frugal

if

you do not work. It also allows for a certain amount of hedonism

without any

particular irony. Such is the prerogative of the young. Some of the

bars are

still there -- bright, glittering monuments to the excesses of cheap

wine and

youth. The music is techno now and the ubiquitous, revolving disco

light has

long been replaced by tasteful halogens. The clientele look the same

though.

Coy, neat young men surrounded by slightly older male poseurs and women

in

retro furs. Back then, the music had always been live. On days when our

student allowance was paid, we would decadently sip liqueurs in that

moody

half-light associated with cocktail bars while Alton played selections

from

Neil Young to Berlioz. Later in the month, when our allowance was

spent, he

would play Billy Joel while I shamelessly begged. It was a fair

redistribution of wealth, we both reasoned.

In the end, poverty and Utopia lost their appeal for most of us as we

embraced postmodernism, travelling in search of new ideals. Alton,

however,

remained steadfast in his views. He recited Mao as easily as he

interpreted

Bach, sometimes even putting "The Little Red Book" to music for the

trendy,

suited crowds who needed to assuage a little of their guilt at being

successful. The belief in sharing worldly goods was equally applied to

his

refrigerator and his bed, many admirers sharing his manifesto for a

while,

but none able to maintain the intensity for long.

At the bottom of the patch there are big, childish raindrops falling

on

top of a cake. The cake has twenty-three candles. Beside the cake,

there is

a mug, white froth piled high. Singing in the rain. The rain on his

parade.

Coffee and cake. The lone guest at his final birthday party.

The last time I saw Alton happy, was in the Melbourne rain. It was a

light,

warm, summer rain that tickled the skin and gave youth permission to

splash

carelessly through puddles. We ran from coffee shop to coffee shop,

savouring the new bourgeois café culture and Brazilian ground beans,

high on

caffeine and wicked decadence and life. We drove up to the Dandenong

Ranges,

singing in tune with the windscreen wipers, our mouths still warmed by

cappuccinos and melting moments. When we reached the lookout, the

shower had

stopped. Tall trees dripped with diamond raindrops. The velvet, green

haze

which makes everything so much sharper immediately after rain cloaked

the

valley below. A rainbow stretched before us, its myriad of colours

defying

the usual spectrum. We found no pot of gold.

Too soon, the music for Alton ceased. He lay in a hospital bed, trapped

by

gnarled hands and a shrinking body. Others in the ward, their minds as

decrepit as their wasted bodies, served as a prophecy for his future.

It

wasn't even a ward as such, just a closed veranda in an old forgotten

wing

of the hospital. Purgatory for those dying from sin. On a bright,

spring

day, we escaped like naughty schoolchildren, hiding behind a giant fig.

There we ate forbidden coffee cake and giggled. Together we wrote his

eulogy, seeking just the right balance of pathos and truth. Enough to

make

people remember, not enough to make them weep at the wake, plenty to

shock

the priest. His words. My words. A final composition. My presence

wouldn't

be required at the funeral he informed me. There would be plenty of

neat

young men and women in retro furs to share the final parting of his

soul. I

sang "Happy Birthday" out of tune and left him sitting beneath the fig,

a

hint of cake crumbs on his thin, cracked lips.

Somewhere in the world there is a quilt. It traverses vast oceans to

weave

its stories of lives cut short. It has seen opera houses in Rome and

blues

bars in New Orleans. It travels to all the places Alton wanted to see,

absorbing the music he would never hear.

I remember the day that Alton died. I was teaching out west. Low mulga

scrub

on the flat, red dust. There had been drought for seven years.

Suddenly,

children ran from the classrooms, lifting their eyes, their faces,

heavenward in bewildered joy. I stood outside too, the unseasonable

droplets

causing me to shiver. And the rain tumbled down.