Patty Somlo

The Rug

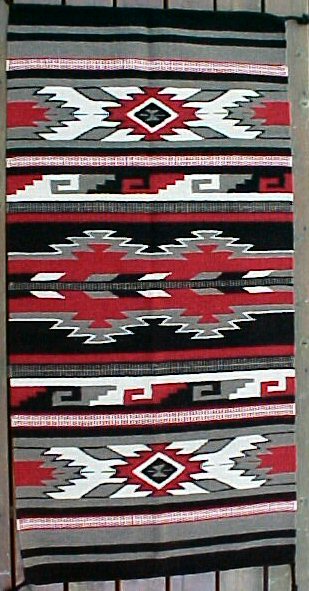

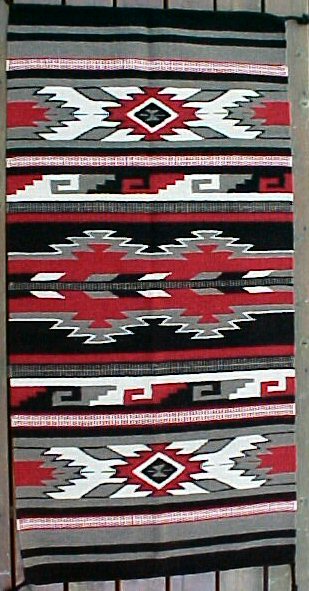

The rug lay in a dark corner of the hotel’s garage facing in the general direction of Mecca. Saeed had bought the rug during a twenty-five percent off sale at Cost Plus World Market. Made of red, green, blue, yellow, black and tan cotton rags stitched together roughly, the twenty by thirty-inch rug sported a narrow nylon label with the name Bolo Chindi on it and the simple fact that the rug had been made in India.

On an April afternoon three months after he began working as an attendant in the parking lot, Saeed unrolled the rug and laid it atop the concrete. No one would notice, he figured. The rug was small, the corner dark. Few cars parked close to that corner because it was the furthest distance from the elevator and the walkway to the outside.

The idea for the rug had come to Saeed several days before, when he was meeting with the refugee program counselor. Her name was Anne and Saeed considered her to be kind, though he didn’t believe his meetings with her once a week made the slightest difference in his life.

That morning the rain was coming down hard, as it did nearly every day. Saeed refused to think of this place as home. He’d left his soaked black umbrella, which was too small to keep anything more than his head and shoulders dry, in a tin bucket next to the front door.

“So how are things going, Saeed?” Anne asked, after Saeed sat down at the table across from her. The lights were way too bright. They hurt Saeed’s eyes.

“Fine,” he said, as he always did, because explaining how he really felt would have taken way too much time.

“Everything okay at the job?”

“Yes.”

“The apartment working out all right?”

“Yes.”

“Is there anything you need?”

“No.”

Then she moved on to the question that each week gave Saeed the hardest time.

“How have you been feeling this week?”

Unlike the previous questions, Saeed didn’t answer this one right off. First of all, the question could not be dismissed with a simple yes or no. Second, and more important, Saeed didn’t feel much of anything anymore, not this week or last week or the week before that. In fact, Saeed couldn’t foresee a time when he would ever feel anything again.

“I don’t know,” Saeed finally said. He mumbled the words, mostly because he knew they weren’t sufficient.

Those words couldn’t begin to explain how bad it felt to be where the sky was always gray and Saeed worried that his feet would never dry. Those words couldn’t touch the deadness in his head, the lack of sleep, or how heavy his body felt getting up out of bed or when he walked.

“Can you find any feeling in your body?” Anne asked him. And then, before Saeed had a chance to respond, she said, “Let’s try doing a little breathing.”

Saeed would never have admitted to anyone that he liked this part.

“Close your eyes and try relaxing your fingers,” Anne said.

Saeed did as he was told. Already, he started feeling better.

“Now let’s make sure we’re grounded. Check and see that your feet are flat on the floor. Back straight. Shoulders down. And then take in a deep breath. Watch the breath as it flows into the nostrils, down the throat, into the lungs, then the belly, thighs, calves, ankles, feet, and all the way out to the big and little toes.”

As he did every week, Saeed lost himself in the breathing. This, of course, was the point after all. To take his mind off the swirling thoughts that made him unable to live in the present moment, as Anne liked to say he should. Instead, Saeed stayed stuck in the past, back home. Yet even there, he couldn’t let his mind remember because there was only the killing and suffering and all the reasons he’d had to leave and come here. And none of that he wanted to remember.

Anne seemed to think he should grieve, that he needed to remember, before he’d be able to move on and live in this moment. Saeed couldn’t tell her that he hadn’t found a reason to live in this or any moment. The best he’d been able to do was put one foot in front of the other, get up each morning and pray. Go to work. Go home. Turn on the television. Sleep. Get up again.

This day, when they were talking after the breathing and before Anne softly said, “We’re going to have to stop now,” Saeed felt a sensation close to sadness. Anne suggested that he find a little something, a photograph, anything, he could take to work, something to remind him who he was. The following day, he went to the Cost Plus World Market because the only cup he had for coffee had broken and he needed to buy another one.

On the way over to where they kept the cups, he passed the rugs. TWENTY-FIVE PERCENT OFF SALE, the sign said. He stared at the rugs and heard Anne’s voice quietly telling him to find something to take to work, a reminder of who he was.

“Can I help you?”

Saeed didn’t know if the voice was talking to him but he looked up. A young woman with smooth straight blond hair and white teeth was smiling at him.

“Can I answer any questions about the rugs?”

“Oh, no, no,” Saeed said, ashamed that his longing had been so obvious.

“Each of the styles comes in three different sizes,” the woman said, even though Saeed had told her he didn’t want any help. “The sizes and prices are listed here.”

She pointed to a square white sign.

“Today only, everything’s twenty-five percent off the listed price,” she added and smiled.

Saeed didn’t know why but he now found himself calculating what twenty-five percent off the price of the smallest rug would come to.

After he paid for the rug and saw that the white paper receipt showed the twenty-five percent discount he’d gotten, the pretty woman who’d helped him rolled the rug into a narrow tube and tied a bright red ribbon around it. The following day, Saeed arrived at work early, pinning the rolled-up rug with his elbow tight against his right side. Before entering the ticket booth, where he would spend the next two hours until his fifteen-minute break and then return for another two hours until his half-hour lunch, Saeed skirted the edges of the parking lot where the light barely reached.

The concrete floor appeared permanently scarred, with gasoline and oil, of course, and substances Saeed didn’t want to consider. Along the walls, though, the floor looked cleaner. He tried to imagine the direction of Mecca, because he’d found a place in one corner that looked the cleanest and where no one was likely to notice the rug.

He undid the bow that nice young woman had tied and thought about how kind she had been to him and her pretty smile. Then he unrolled the rug, placed it on the concrete and smoothed it down.

A maid named Lydia Sanchez spied Saeed the next evening as she walked to her car. She was in a hurry to get home, as her mother had been watching the kids and would be tired by now. But there, in the corner of the parking lot, Lydia spied a tall skinny very black man, bent over on what looked like a beach towel or maybe a small rug.

“Enfermo,” Lydia whispered. He must be sick.

Yes, Lydia needed to hurry but she also had compassion for children and the elderly, animals and the sick. She dreamed of one day becoming a nurse, if she could ever get a green card. The man looked like one of the parking attendants. They were all black, with the blackest skin Lydia had ever seen, and she’d heard they came from the same country in Africa. One of those places where people were fighting all the time, so the parking attendants were forced to flee and become refugees.

The short, slightly pudgy maid walked to the corner of the parking lot, instead of climbing into her car as she’d intended. As she made her way there, she tried to find the English words she needed, but at the moment, the Spanish words kept pushing them away.

Just before she reached the corner, the word came to her.

“Sick?” she asked the man.

He didn’t answer right off and Lydia started thinking, Who should I call? Who should I call? She was in this country without papers, having gotten the hotel job with the use of a phony Social Security card. She could dial 9-1-1 and then hop into her car and drive off, before anyone arrived. That’s what she could do. But first she bent over and asked the man one more time.

“You sick?”

This time, the man who Lydia could see now was long, long, long and thin, like spaghetti stretched out, and his chest rose up. He looked at her while he still had his legs folded underneath him on the rug.

“No, no, no,” the man whispered to her, as if his condition was some sort of secret. “No not sick.”

Lydia wanted to ask what he was doing there, practically laying down in a corner of the parking lot. He wasn’t homeless, like all the people that sat on the sidewalks for blocks around the hotel. Lydia recognized him from the ticket booth, saying Hello and Thank you to her when she handed him her pass, driving out after work. Yes, she had always thought he appeared to be a nice man and wondered sometimes what he thought about living here in this country. How different it must have been from where he’d lived in Africa.

“I thought you being sick,” Lydia said now.

“No, no, no,” he said again and then surprised Lydia by adding, “Just praying.”

“Praying?”

Lydia let the word hang in the air as she thought about it. Lydia prayed at church every Sunday morning and at night, before climbing into bed. When one of her kids was sick, she silently asked God for help. “Por favór Dios,” she would mumble to herself. She prayed, yes, but never in a million years would she have gotten down on her knees in a parking lot, closed her eyes, folded her hands and whispered the words Por favor Dios, Please God. It made her heart ache thinking about this man and what terrible sickness or hurt, tragedy or pain had brought him to this place.

The man was waiting for her to say or do something. Lydia could see that. What could she possibly say in the face of such suffering?

“I hope God answers your prayers,” she said.

Most of the time, the rug lay in the corner of the parking lot, as if it had been abandoned, like the cigarette butts and used tissues and crushed cans scattered here and there on the stained concrete floor. Other than the maid, no one noticed the five foot ten and three-quarters slender man, with high prominent cheekbones and close-cropped wooly hair, who knelt on the rug and prayed in the general direction of Mecca. The man, Saeed, understood that this simple act might be seen as threatening to some, and for this reason he put the rug in the darkest, most remote corner of the lot. It was worth the risk, he soon discovered, because in moments of prayer, for the first time since leaving his country, he started to feel whole.

Nevertheless, the maid felt burdened by the knowledge of the African’s suffering. She couldn’t keep what she’d seen to herself. And so the next morning when she arrived bright and early to work, she whispered the news to another maid, Esperanza. Of course, Lydia changed the story a little. She said that the African man was praying because his wife was sick. He was asking God to make her better.

The story then went from Esperanza’s lips to the ears of another maid, Carmen. From Carmen, the tale wound its way from room to room and lower floor to upper floor of the hotel. Eventually, as such stories do, the tale made it all the way to the hotel’s kitchen. A dishwasher named Eduardo heard it first. By this time, the African man’s wife had died.

Being a man, Eduardo had trouble hearing of the African’s suffering and not doing something about it. When he told the story to Efrén, another dishwasher, he added, “Maybe we should take up a collection for the African.”

Having little extra money and not yet moved to part with some for an African man he had only exchanged a handful of words with, including, How you doing man, Efrén said, “What is money going to do now that his wife is dead?”

Eduardo, who everyone in the kitchen knew would have given his last dollar away if he thought someone needed the money more than he did, said, “He can use it to help pay the bills.”

The story spiraled around the kitchen and then bumped out to the dining room on the lips of the busboys. In a sense, it was as if the tale was making its way around the entire world. Having begun in the parking lot where all the employees had originated in Africa, the story shimmied into the hotel rooms, settling down for a few minutes with the maids, who hailed from Mexico and Guatemala. The tale was passed on in Spanish to the dishwashers and prep cooks and afterwards to the busboys. And then the busboys, in broken, heavily accented English, told the waiters and waitresses, from France, Italy, Great Britain, Ireland and Canada. By this point, the African’s wife was long dead, and his three young children had no one to take care of them during the day, while their grieving father took people’s money for leaving their cars in the dismal lot.

Saeed, of course, knew nothing about any of this. The return to prayer, along with his weekly counseling sessions, watching the breath traveling through his body, until it connected with that well of sorrow and loneliness, fear and rage, lodged in his belly, had begun to lift Saeed’s spirits up. At the same time that his mood began to lighten, the world around him seemed to respond. Other employees who had previously tossed him a quick Hi or How’s it going, when handing him their yellow staff passes through the half-opened windows of their cars, suddenly began addressing him by name and taking an interest. “How are you doing today, Saeed?” “How is everything at home, Saeed?” “Is there anything I can do to help you, Saeed?”

The unexpected interest and hearing these strangers address him by name caused Saeed’s heart to open a tiny bit more each day. At first, Saeed simply responded, “I am fine, thank you.” But after his heart began to crack open a bit more, he turned the spotlight of his interest on others. “And how are you doing today?” “What is your name?” “What country do you come from?”

The rain continued to pound the pavement, the hotel roof and the roof of the building where Saeed rented a one-room studio apartment and heard music and a couple making love and another couple arguing and a baby crying through the thin walls and sirens wailing all night, up and down the wide, yellow-lit boulevard. Rain kept making brown muddy puddles in the potholed roads and cracked sidewalks, forcing Saeed to leap across, in order to keep himself from sinking. He stopped carrying an umbrella and simply yanked the hood of his waterproof nylon jacket up, as he’d seen all the local people doing. The rain didn’t make his forehead feel stuffed with cotton, as it had before. And he began to think, I don’t mind the rain so much anymore, and even found the sound of it tapping the windowpane at night rather soothing.

A building supplies saleswoman attending a construction conference in the expansive Douglas Fir Room on the hotel’s main floor and staying in a teensy room overlooking the alley, miles from her Asheville, North Carolina four-bedroom, three-bath home, noticed Saeed praying in the general direction of Mecca. It was a Tuesday afternoon, and at that very moment without a bit of warning, the sun had shot out from behind the clouds. The woman whose name was Shirley Clooney had just stepped out of her rented Ford Taurus, the same make and model of the car she drove at home, when she spotted a dark-skinned man lurking in the corner of the garage.

On seeing him, she clasped her oversized black patent leather handbag tight to her chest, while her eyes darted around the parking lot, in search of the elevator. Her brash red hair shone under the garage’s fluorescent lights and her swollen feet ached in a pair of new black leather pumps. Her heart rattled high in her chest, as she fiddled with her phone, ready at any moment to punch in the pre-set number for 9-1-1.

Shirley could see now that the elevator was closer to the dark lurking figure than she would have liked. Her feet sounded like bullets tapping across the concrete floor, walking as fast as she could, wondering why such a fine hotel didn’t have security guards, at least one, in the garage.

As she got closer to that dark corner, she saw that the man was not, in fact, lurking in wait to rob her. No. He was, what, laying down on a little beach towel or rug? Shirley looked more closely. Then she mouthed the words. Oh,

my God.

It was just like on TV. When they showed the mosques, filled with men, all men, Shirley thought. Up and down. Praying to Allah.

Like a bomb, the information exploded across Shirley’s mind. A man in the hotel garage praying to Allah means only one thing. Don’t they always pray before blowing themselves up?

Shirley picked up the pace, her heels rat-a-tat-tatting faster across the stained concrete floor. Breathless, her heart pounding, she hit the elevator button almost hard enough to break it. The door instantly opened. As soon as the door closed, Shirley punched in the pre-programmed number for 9-1-1.

By the time the police cars arrived outside the garage in a wailing symphony of sirens, along with the bomb squad in a huge white truck, Saeed was back in his booth collecting tickets, running them through the machine, giving back change and saying, “Have a nice day.” Police officers in black helmets sprinted past the booth, not bothering to even look Saeed’s way. Saeed couldn’t have said how many ran past in their dark blue uniforms. But relating the story later to anyone who asked, Saeed said, “Maybe fifty.”

The next thing that happened was that officers stationed themselves on both sides of the ticket booth, talking with the drivers and looking into cars going in and out. None of the officers said a word to Saeed, who continued taking tickets and money, and occasionally Visas and Mastercards, and sometimes giving back change. Under the circumstances, Saeed thought it best not to tell anyone to have a nice day.

©2014 by Patty Somlo