Dean Ballard

Thirteen and Spring

Topper Lane spent the night in jail for buying a joint at Tiger Stadium. He was the "bad influence" feared mostly by the parents of Harper Woods. My friend Trig and I spent much of our teenage years in Topper's flat above his father's garage.

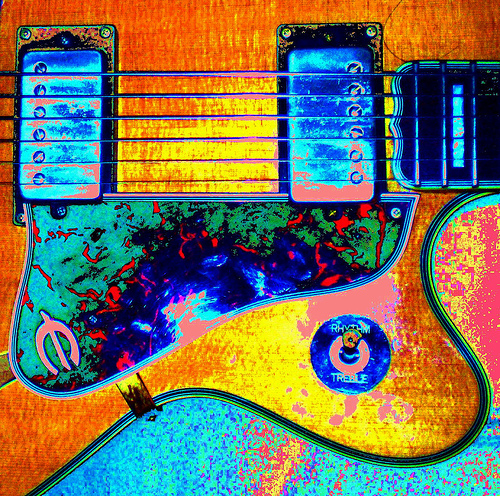

There in the gray aluminum-sided, two-story fun house on Beaconsfield and Roscommon, we'd listen to records and peruse Rolling Stone magazine. Topper's flat was where I first smoked pot and felt a girl and learned how to play guitar. It was also where I discovered the pure soul of country music, and learned how deeply entwined it is with rock and roll. From Topper's turntable we discovered that one form -- much like true love -- cannot live without the other (The lesson plan came from Buddha James, but Topper's flat was where the tune-dissecting began.)

"Would Elvis ever have even happened if there was no Hank?" wonders Trig as we sit Indian-style around Topper's turntable one day after school, in a trance watching the black circle spin "Mystery Train."

"And would Hank have happened if there was no Tee Tott?" says I, hypnotized by Scotty Moore's electric guitar and Elvis Presley's rhythm. We're walkin', talkin' like wild, eccentric, music historians conversing over creation or Heaven as we go back -- one succinct observation after another -- back to the beginning of time where we find Elvis' bass player, Bill Black, slappin' his double-bass drive for the young soul rebel beat, part of something new and timeless. Trig's wearing a pair of freshly polished cowboy boots. Topper and I are in our usual Jack Purcells. We're like two Ramones sitting next to Levon Helm talkin' shop.

"And why was the so-called King shaking hands with Nixon in the Oval Office?" adds Topper with a suspicious tone.

"Yeah, Son," laughs Trigger Man. "The thing about music is the more you know the less you know," looking right at me with his sly, country-boy bloodshot eyes. "Elvis should've been up on the roof smokin' a joint with Willie. I know I would've," trailing off into mischievous, high-pitched laughter. And this is how many of our round turntable listening sessions would roll out into one unbelievable and wondrous Midwestern hue filled with seriocomic dialog on the origins of country rock or America or side-tracking upon Rosa's thighs.

But when it came to Detroit music, which I will forever hold dear to my heart, our conversation would almost always begin with Mitch Ryder and The Detroit Wheels. True how they bowed to their British betters, but valiantly, along with The Funk Brothers, brought to life the sound of Detroit.

The Funk Brothers...ah, yes, those insanely talented, yet mostly unheralded godhead-musicians... "You can talk about the room they recorded in all you want, that sound came from their hands!" Topper insists.

"The Sound of Young America," the music of our parents -- food for The Beatles and The Stones -- became so ingrained and threaded throughout our days with masterful street tunes like "Money (That's What I Want)," and "Devil With The Blue Dress," and "Baby Love" -- the joyful beat and sexy voice of Diana Ross -- the loose, soulful Pappa Zita high-hat -- street music gems elevated beyond belief when sculpted by the hands of masters.

Four wooden steps lead you down to the "Snake-Pit" at Hitsville U.S.A. -- "the bridge to dreams" I hear Jack Ashford's tambourine shake. It was a holy place where Motown's in-house studio band would together dwell and smoke and create magic under cool, dim lights. They were the baddest, and provided Stevie Wonder, Marvin Gaye, Smokey Robinson and his Miracles, The Supremes, The Temptations, and The Four Tops with an unshakable foundation amidst the Detroit night chaos. The Funk Brothers were Joe Hunter (band director, down-home "Pride and Joy," "Shop Around" piano), James Jamerson ("a genius on the bass," as described by Motown founder Berry Gordy, played his classic "What's Going On" bass line while lying flat-on-his-back drunk), Robert White ("My Girl" guitar, as recognizable as "Satisfaction" or "Come As You Are"), Earl Van Dyke ("gorilla-style" Hammond B-3, earth-moving "I Heard It Through The Grapevine" organ), Eddie Willis ("Signed, Sealed, Delivered, I'm Yours," "You Keep Me Hanging On" jazz man guitar), Joe Messina ("Dancing In The Street" Soupy Sales guitarist of Motown's "Oreo cookie," sat in the studio between White and Willis), Bob Babbitt ("Inner City Blues" -- "That's Babbitt, man" the 12th Street bass players shriek), Jack Ashford (cool Miles Davis on the tambourine), Uriel Jones (original fill-in for Benny Benjamin, hard-hitting, funky "Aint No Mountain High Enough" drums), Eddie "Bongo" Brown, Richard "Pistol" Allen, and Benny "Pappa Zita" Benjamin.

But when Trig, hovering over Top's turntable, drops the needle on "Shake A Tail Feather" by The Detroit Wheels, the conversation ends. All that's left to do is surrender to the beat, the indomitable drive: the spirit of the people.

Mitch Ryder shouted like a lunatic greaser racing down Woodward Avenue in a '66 Mustang at night. This is where it begins if you're a white rock and roll kid from Detroit. From there you move on to The Stooges and The MC5, cross over to The Romantics, then leap right into The White Stripes and The Dirtbombs.

At the start of the 21st century I certainly represented the old guard, someone who had fallen off of his pedestal as part of the Flying Machine country-rock scene of the '90s. Feeling quite removed from my surroundings, I'd sit on a barstool every Friday night at the loneliest east side bar I could find and tell old war stories about the local, legendary Thieves. My worse moment came back in 2002 with my old bandmate and drinking buddy. Isiah Cooley was the virtuoso who turned from guitar to pedal steel about two years before joining The Thieves. Isiah was brought in by Smoke, who told Topper that the only way he'd join the band is if he could bring Isiah with him. The deal was done. Many years later, Isiah would become a session player for the burgeoning "garage" scene and I'm sure felt out of place, since both him and Smoke grew up on pure country music: George Jones, Merle Haggard, Johnny Paycheck, etc.

In the fall of 2002, we were, per usual, getting drunk at The Flying Machine on Kelly Road.

Isiah Cooly and I were great friends back in the day and shared the same ideas about music. To my surprise, he found his way into a crappy garage rock band at the turn of the century, about six years after the bullet shot through the brain of Kurt Cobain. What it really came down to was that calm, cool Isiah had the good sense to cultivate certain relationships that I insolently turned my back on, dismissing an entire movement without realizing its global impact. In other words, I just didn't get it -- the whole garage rock revival of the early 2000s. And I'd rather not discuss my most embarrassing moment. I'll just say that when I now listen to Jack White's masterpiece, "Dead Leaves and the Dirty Ground," I can hear the greatness.

"...every breath that is in your lungs

is a tiny little gift to me"

Pure Dylan. Pure Poetry. I place it right up there with Hank Williams or Townes Van Zandt.

Now don't get me wrong here, this rant isn't about all that. It's about something more than aesthetics. It's about a precious moment in time when all was new and we were boys trying to walk like men, and all that mattered in the world was a song.

Ah, once I was thirteen and it was spring.

©2014 by Dean Ballard