Night Terrors

by Megan Doney

Someone’s intestines are on the beach today. It may not be someone, exactly—the greenish, twisted pile is too small to have belonged to a human being. I kneel down on the sand to examine it. I have never taken anatomy or biology, so I’m not sure what to look for, but I’ve never seen entrails close up. These ones are long and fat, a pleasing pale blue-green in color. The heady smell of decay rises from them like fog off of the sea, mixing with the scent of Coppertone and coconut.

Already the morning sun is hot on my shoulders. The heat bores through the thin film of sunscreen that covers my body, and I imagine infant malignant melanomas exploding like tiny galaxies in my skin, skinny tendrils swirling outward and outward in deep shades of red and gold. I stretch the flesh on my arm and poke it, suspiciously looking for new freckles. Great. So now I’ve got skin cancer to accompany my carpal tunnel syndrome, trichotillomania, brain tumor, and detaching retinas.

My father comes down to the beach from our condominium, carrying the beach umbrella and two chairs. As soon as he has the umbrella up, I move my chair into the shade and rub on another layer of sunscreen, though I haven’t even been in the water yet.

“C’mon, chief,” my father says. “Let’s go in.”

My father is a former lifeguard. I feel okay going in the water with him because I know that if I begin to drown, he will save me. Even if I’m chomped in half by a great white shark, I know that he will try to kill it with his bare hands. I get up and walk with him to the shore, getting my toes wet before I’ll go in any further. Toes—ankles—knees—thighs, I cringe—waist—armpits. My father dives in and swims past the breaking surf to where the water rolls and bounces like liquid glass several yards from me. I stand in the shallows, doing the coldwater dance, bouncing from one foot to another, waving my hands over my head. There are not very many people in the water this morning, despite the hot sun and the thick humidity that lies like wet Kleenex over the beach. Dozens of jellyfish float in the green water, small to medium red globes straggling skinny tentacles. I imagine diving under like my father did, eyes closed, cheeks puffed, and swimming right into the gelatinous body of a jellyfish. I picture it clinging imploringly to my face and stinging my eyes and tongue, eating my skin away like acid.

Something out here is missing its guts.

“Wuss!” my father yells, as he floats on his back and looks at me, laughing as I do my desperate dance. I take a deep breath, squeeze my eyes shut, and dive underwater, kicking hard towards him. Only the sea washes over my face as I surface, smiling.

Later, we squat on the sand looking for shells. My father collects seashells at the beach, squirreling them away into the pockets of his swim trunks. In the afternoons, he likes to take long walks, jingling the shells in his pockets the way that some people jingle loose change. Sometimes he gifts them to people, usually his students, at the end of the year when they graduate. Today he sits back on his haunches examining the bits of shell mixed with sand and water. I am on all fours, waving my butt in the air as I inspect each small stone. There was a storm the night before, and a multitude of shells and stones washed ashore. In the sun, the sparkling bits look like careless shards of crushed Christmas ornaments. I pick up stones like grains of salt, with translucent sharp edges; pale purple spheres; blue-grey chips of clam shells. In the sand too are empty twin black mussel shells, abandoned by their softbodied inhabitants. The inner lining shimmers like puddles of gasoline.

I use my hands like ice cream scoops, digging holes in the sand as the sea rushes forward to fill them up again. Something scrabbles in my hand; I’ve scooped up a sand crab and its legs plow through the air as it tries to get away from me. Pinkish-grey-shelled, eyeless, I hold it up and watch the insectoid legs claw, then slow, and I hurl it hard back into the sea, wanting to get rid of the crinkly claws on my skin, remembering a nightmare of maggots squirming on dead flesh, screams.

My father goes for a walk around three. Dozing alone on the beach under the umbrella, hot wind blowing around me like a memory of the desert, the swirling colors behind my eyes remind me again of those melanomas in my skin, glowing like an aurora, and I imagine tiny cancer cells like asteroids flying through my body. Asteroids are not known for their finesse; they clunk and skip across space and collide with other bits of space-junk. The cancer cells are in there too, racing like NASCARS and shoving surprised, healthy cells out of the way. The images of my cancer weave through my mind as familiar as old socks. I slip inside them, warm and snug, and settle in to watch the show, fluorescent cells careening through the black.

I stay on the beach late into the afternoon, after my father has gone in. After five o’clock (the end of peak UV hours) I feel okay coming out from under the umbrella, and I lie on my back and stretch my arms above my head, my shoulder blades digging crunchy hollows in the sand. The breeze plays on my stomach and thighs like a lover, and I remember a man with laughing brown eyes and a Chinese tattoo on his ankle burying his head between my legs as I stared up at the South African flag on his wall, yesnoyesyesgodyesafricaaidsgodgodnoyesnonono

And afterwards, remember squatting over a mirror in my bathroom every day for the next month poking and kneading the tender tissue looking for some sign that yes, I have syphilis, chlamydia, gonorrhea and all those other diseases with names like flowers. I am too rough and my thumbnail peels off a pink film of skin, leaving me torn and bleeding. I jam two fingers deep inside, feeling for invisible lesions, for the maggots, and wish that I could rip out each organ, fairy-thin fallopian tubes, melony uterus, ribbed thumping vagina, and lay them all out on an examining table so that I can see, see where the AIDS and herpes and warts are hiding, waiting to emerge and to mark me.

The inability to see is where the terror lies. The body. The ocean. The night. Then I only have my imagination and the nightmares coiled and hissing like snakes are worse than anything the daylight could bring. I’m twenty-six years old and all I can think about is my own death.

It is a Ptolemaic view of my universe, I know, as if my body was the axis around which all things revolved, as if every germ in the world was on a collision course with my body and only my body. Dying ought to be the last thing on my mind. I’m thin. Not tan. A runner. I like vegetables. But I am scared to fall asleep at night, afraid that a silent cerebral hemorrhage will kill me. On airplanes, I panic, feel dark blood clots sticky like raspberry jam in my legs. A headache equals bacterial meningitis. Bone cancer. Multiple sclerosis. Heart failure. My universe is populated with asteroid cancers, heart attacks exploding like supernovas in my chest, white painless aneurysms with feathery tails like comets. Every ache and twinge in my young body is the summoner’s call.

I know that this degree of hypochondria is crazy. When I can see clearly through the starry mist of cancer cells I know that I am wrong. But I believe that if I think about my own death enough, it can never sneak up on me as it does for so many people—I can surprise it, can turn around and shout in its face, “Hah! I saw you coming! You can’t get me!” And then death will grumble and slink away empty-handed. And I will laugh.

But then I see myself staring into a full-length mirror, examining my naked body from every angle. Pale, yes, pasty, my sisters would say. Unmarked, slender, serviceable. Passably attractive. But who knows what is happening in the red and yellow and black jellies inside, lurking in tissue folds and hiding behind each organ? Skin deceives.

“Look at this one!”

My father holds up a shell streaked with amethyst at the heart. He grins, satisfied, and pockets it, standing and wincing as his back uncurls. Some lucky kid will receive that shell at graduation next year. I look down at the sand and see piles of hair blowing gently in the wind, hair that I’ve plucked out of my own head.

I go for a walk later in the afternoon. Sleek young couples my age lie supine on gritty towels, faces expressionless as their skin browns and bubbles. I stare at them enviously. None of them seem to be pondering their deaths. I stop to watch the water rush past my feet, white and fishy, stuck in the brown sand. The ocean eats people.

Under clean white sheets, I try to sleep in the dark living room that night. I lie as still as I can, but feel the ocean’s ghostly rhythm rushing through my bones like the tides, carrying me out past the breakers to cold inky depths. In a night sky in the middle of the sea, stars flicker like dying candles. Like dying cells. Behind my eyes I again glimpse the shimmering cancers spinning and spreading farther and farther out, waiting in the shadowy crevices of my body. My head hurts. Nothing is ever just a headache.

I am not even afraid any more, though my body goes through the motions of terror. The notion that these are my last moments on earth is so familiar that I can almost burrow into it like a sleeping bag and relax while the panic takes over. I can’t catch my breath and I’m alone out there in the ocean, struggling like a dog to keep my head above water. I am cold all over, frozen like Han Solo in carbonite. I press two fingers to my wrist and feel for my pulse; it is warm and fast under my skin. My crimson heart pulses like a jellyfish in my chest, frantically expelling blood as water, only I know that the aneurysm in my brain is going to stop it any second now and I screw my eyes shut, see the maggots again squirming from the warm places of my body, wonder if I’ll see the long tunnel with light at the end.

Minutes must pass. The blood-bright lights on the alarm clock read 2:37. I am not dead yet.

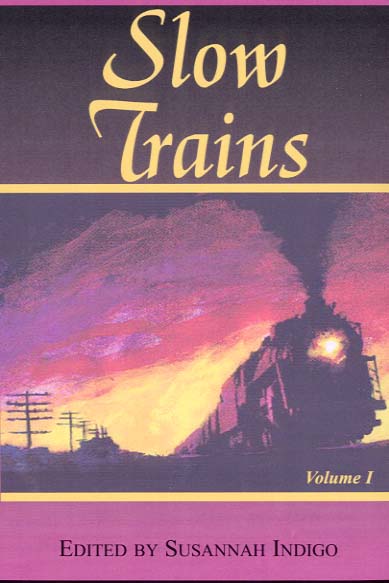

Slow Trains, Volume 1 in print

Slow Trains, Volume 1 in print