|

Notes from A White Mother Raising a Biracial Son by Alana Noel Voth

“You’re brown on the inside,” I tell him. “The Daddy who helped make you is brown.” As soon as Kellon was born, others began to comment on his mixed parentage, as I suppose they considered their right when visiting the new baby the first time. “He doesn’t look brown. How brown is his father?” “He looks white to me.” When I was pregnant, I dyed my hair black. My mother said, “Well, it’s...dark, isn’t it?” I pictured my son before his birth: he looked like his father. I imagined a tiny, placenta-slick baby sliding from my womb and into a doctor’s cupped hands and hearing a nurse ask, “Whose baby is this?" Dying my hair was the best I could do. The Daddy who helped make him was not on Kellon’s birth certificate. I told a friend, “Call Michael and tell him our son was born.” Michael challenged paternity. But the blood inside told the truth; the blood inside was mixed. Kellon was Michael’s baby: Michael’s and mine. The father’s name was added to the birth certificate. I went back to blond. I wanted a child that was part me and part Michael. I daydreamed Kellon arriving with a glow to his skin that made the announcement: I’m both. After the cramps and blood and crying, there was a baby who looked like any other baby, and his eyes regarded me like he was startled, and then I held him to my breast and he fit there, and I was thankful because he was whole, had all his fingers. Later, like in the moment when you wake from a falling dream, or when you’re on speed or something, I decided that Kellon’s life would benefit from my going head to head with the pessimists, the racists, my own family, and I declared my son the mighty warrior, guerrero poderoso, a fucking miracle. Hope. Someone said, “You’re making a big deal out of nothing.” Someone else said, “Where’s this fucking Michael guy? I don’t see him anywhere.” It became worse and worse that Michael was an absent parent. No one would see Michael when they looked at his son, including his son, and so the falling dream was suspended while I debated was it worth it, fighting for what existed only in blood? On the 2000 Census form, "biracial" wasn’t an option. There wasn’t even an option, if you’re Hispanic and Caucasian, check here. I found a box at the bottom called Other. What the hell is Other? Why aren’t the rest of us one of those? It seems nondescript, as if one Other could be like the next Other, and the Other next door to him. My son is an Other, and this is hopeful. But there’s shit on the streets. People used to ask me, “Why don’t you stick to your own race?” and Michael was called a Want-to-be-white-guy when he dated me. It was never completely normal. As a child of a mixed union, Kellon may decide to go with what people assume when they see his light skin and last name. Someone told me that since Kellon looks white, life is going to be easier for him. He might not decide to go with what’s harder. I imagine a moment when Kellon’s brown friends, Roy and Jacob, don’t want him, or he doesn’t want them, or they simply don’t identify anymore, and Kellon will settle down with the other white boys, and he’ll find it curious, maybe cute that he used to ask me, “Where’s my brown?” and he might miss the irony when I tell him that blood, when it hits the air, is always red.

©2002 by Alana Noel Voth

Alana Noel Voth is earning her MFA in Creative Writing at

the

University of Oregon beginning September 2002. Her fiction,

non-fiction, and poetry have appeared in Metrosphere and Element Magazine. Her alter

ego, Lana Gail Taylor, is doing better writing erotica.

|

| Home | Contributors | Past Issues | The Ten | Links | Guidelines | About Us |

|

|

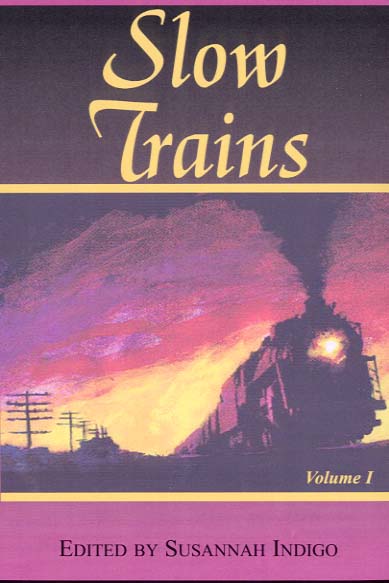

Slow Trains, Volume 1 in print Slow Trains, Volume 1 in print

|