Mazzonelli's Masterpiece

by Phoebe Kate Foster

The man across the street has a bad reputation. As soon as Sandy moves into her new apartment, she hears the gossip about Mazzonelli from the neighbors. She knows all about bad reputations. They spread like a red wine stain on a linen tablecloth and are just as indelible. In small towns, a fall from grace is as irreparable as an apple parting company from its tree branch.

It’s always the same old story, Sandy thinks, just with different names.

Always from a good family, of course. Always the same old tired excuses: married the wrong person at the right time, the right person at the wrong time (does it really matter?) Always a list of woes: financial troubles, drinking problems, difficulties on the job. Always troubled, turbulent children (are there any other kind?) Always fights, getting ever more violent as a couple explores uncharted realms of rage.

Always affairs. (Are we just sloppy sneak-arounds or do we really crave to get caught?)

More fights. Police at the door. “Your neighbors called to report a domestic disturbance here.” (You cringe, and crawl deeper into your skin.) Scandal is like a bad smell. (You see them turn away as you pass by, pretending not to see you. You have contaminated their polite world with the reek of your untidy life, which they will neither forgive nor forget.)

For the children, for the sake of a good name, there’s always an attempt at reconciliation. For a brief time, the house is baptized with the unnatural hush of a church, as a husband and wife on their way to becoming total strangers tiptoe through each day, reverently reciting the remembered firsts of a shared life, like the words of a creed that will at last make two people one (the first time we met, dated, kissed, made love…our first home, Christmas, baby…our special song, restaurant, holiday…walking in the woods…dancing on the beach…the sun on my face, the moonlight in your eyes, the plans we made, the dreams we spun)—until the frail veil of peace is inevitably rent by a curse, a slur, a slap.

And then, the final blow-up. (Never like in the old movies, is it?—civilized and bittersweet over cold dry martinis in mellow lounges with satiny music and sad regrets and exquisite exits) but crude and primitive, the resounding scream of the mortally wounded marital beast. Darwin’s process of evolution reversing itself in a single moment—enlightened man and liberated woman reduced to tooth and claw, jaws locked in a death grip on the other’s soul, each struggling to be the first to draw the last drop of blood from a dying relationship.

And when it is done, all that remains are the cold bones of court and custody hearings, and the clacking of tongues rehashing ruined lives as an afternoon’s recreation.

Sandy learns that whenever Mazzonelli’s ex-wife runs into him, she screams, “Don’t come near me, you monster, or I’ll have you sent to jail for the rest of your rotten life!” He lost his fancy wine-and-cheese shop after the divorce. “Nobody wants to buy their Beaujolais and Brie from an abuser,” the neighbors say. “He now works on the loading dock of the shoe factory. With his reputation, he's lucky to be working in this town at all.” (Me, too, Sandy thinks, when she hears that remark.) His children, when they pay their infrequent visits, are in the constant company of a social worker, drab as a cockroach and shrewd as a rat, always searching for a crumb of impropriety in Mazzonelli’s manner.

He doesn’t keep up his property anymore. Eating her fourth microwaved diet entrée in a row, Sandy stares out her window at unraked leaves on the unmowed lawn and dead shrubbery huddled against the broken fence, and watches the sad little man shuffle through the shadows to his empty house. He’s as gray and lifeless as the winter evening. “Got what was coming to him,” the neighbors all say.

Sandy knows her former neighbors in the fancy suburb just outside of town are saying the same things about her. “Why, do you know the judge refused to give her custody of her own children and you know that mothers always get the kids—unless, of course...” letting their voices trail off meaningfully.

From her bedroom, Sandy can see into Mazzonelli’s bedroom. When there's nothing good on TV, she sits in the dark by the window and watches him. Every night, he paces and drinks, then passes out fully dressed on the bed, sprawled with the gracelessness of a dead man. He wakes at 3:00 or 4:00 a.m. and gets up to pace some more, have another glass of Scotch, another cigarette.

Sandy's awake then, too. (The blessing of a good night's sleep is denied us sinners, of course.)

Tonight, as Sandy lies in bed eating a carton of chocolate chip ice cream, an eerie radiance suddenly dispels the darkness outside her window.

(A fire? No, not the right color. A vision of Mary in her starry blue robe? Sweet Jesus’s shimmering globe of godly face?) She was raised a Catholic, trained to hope for miracles, look for signs. (Hell, I’ll believe anything.) She’s a big girl now, though. She isn’t expecting much. She knows quite well that God and His perfect family only pay personal visits to saints.

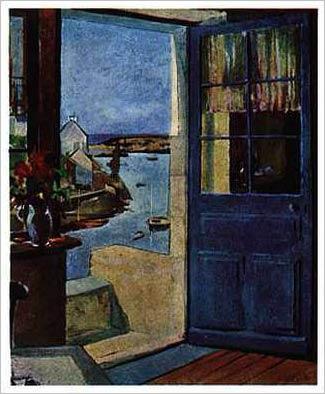

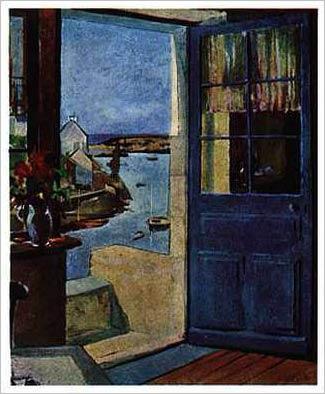

When she looks out the window, what she discovers is as breathtaking as a theophany. Mazzonelli has turned on some sort of magnificent light that inundates his bedroom with the brilliance of a thousand candles reflected in multicolored mirrors. The glow spills out into the street, filling the night with shimmering blues and golds and greens. (Ahh! Summer day and fall sunset and Christmas lights all in one...)

Instead of slumping on the bed and polishing off a fifth of Scotch, Mazzonelli works on a craft project, which is quite large and rests in a frame on a floor stand.

(Embroidery? Weaving? Odd hobby for a man like that. But you’ve got to do something to fill all the lonely hours…)

She finishes the carton of ice cream (he creates, I eat…) and gets her binoculars for a better look. (Latch-hook. Of course.)

The piece is almost done. It has a striking pattern—a huge single flower on a neutral background. The more closely she examines it, though, the more distasteful the design becomes. The flower is grotesque, resembling a gaping, bloody wound. The petals have the raw, ragged look of torn flesh and the pistils protrude like shards of broken bone. Sandy watches Mazzonelli labor over the hideous thing with the desperation of a doctor trying to suture shape and sense into the unseemly chaos of a fatal injury. Finally, he steps away to survey his work, pacing and raking his hands through his hair, rubbing his eyes as if they hurt.

He throws his head back and utters a scream so piercing that Sandy can feel it through the closed window as it rattles the pane like a tremor. Arms outstretched, he lunges at his creation.

(He’s going to rip it apart…)

Instead, he presses his palms against it and bows his head, like a priest presiding over an unidentifiable body, laying on hands, hoping to will life and order into what is mutilated beyond recognition.

Sandy shakes her head and goes to the kitchen for something more to eat.

The next night, Mazzonelli’s mysterious light again filters into Sandy’s dark room.

She peeks out the window. The latch-hook project is gone. Mazzonelli stands on a ladder, painting a mural on the walls and ceiling of his room. Sandy wonders why nobody bothered to mention that the bad man across the street is an artist.

(Oh well, same reason nobody remembers anything about me, of course, except I cheated on my husband, neglected my children, then gained thirty pounds after the divorce was final and my lover dumped me for someone else.)

Sandy examines his creation through her binoculars. (Ah, Mazzonelli, you are indeed a DaVinci, a Michelangelo in the making. But your subject matter...)

It’s an angry scene he depicts. Not the sweet hand of the Father extended to Adam but a fist crashing through the thin eggshell of fragile lives. The rays of sun drip like blood, the sky is livid as bruised flesh, the earth is hurt and disheveled, the world ripped and in ruins. Balloons float up to the sky and incinerate like the Hindenburg. (My God, those aren’t balloons, they’re faces!) Mazzonelli paints them again and again until the room is covered with the flaming record of unspeakable pain.

Though she wants to draw the curtains, though she wants to go to sleep, Sandy is compelled to watch until he slumps down on the floor and covers his face with his hands.

(Jesus, is he crying?)

Night after night, he works on the mural and weeps while Sandy watches.

Sandy can't stop thinking about Mazzonelli. (The neighbors are right about him, of course. He’s a bad man. And obviously crazy, too.)

She fantasizes about visiting him. (I’ll show you bad, mister. Ask my old neighbors out in Brandywine Park. They’ll tell you I invented bad. And crazy. They all said I had to be crazy to throw away my life the way I did.)

She’ll knock on his door tonight, she decides, dressed in something that commands a look, invites a touch. She’ll buy a bottle of good wine for them to drink. She’ll explain that she noticed he was working on a piece of art and she’d like to see it, for it does look most intriguing—like a woman who is either very beautiful or very ugly depending upon the angle of viewing, and is therefore ineffably and indescribably fascinating to the eye—and she would greatly appreciate a closer look because she is someone who can be trusted. (I’m not like the wagging tongues in the neighborhood. I truly do understand.)

(Well, I won’t exactly say all that.) Instead, she’ll convey the sentiment with eyebrows that remain steadfastly unraised and a voice that is knowing but kind and a gaze as transparent and telling as broken glass.

But that evening, she consumes her many diet dinners and drinks the wine she bought for Mazzonelli while she watches him frantically fill another wall with the mural.

(He’s demented. Taking the sacred dust of the earth and turning it into something grotesque.) Black suns. Bleeding moons. Lidless eyes. Eyeless sockets. Skeletons standing in groves like old dead trees. Horribly deformed babies, best kept away from the light of day like dark secrets. (The landscape of a living hell.) It all seems eerily familiar to her, like a nightmare she doesn’t care to recall. (It is the ultimate act of immorality, giving pain a face and suffering a form.)

Mazzonelli stands in the middle of the room, stained with paint like blood, and stretches out his arms like a crucified man, embracing the horrible creation surrounding him on every side.

Horrified, Sandy turns away.

There's no sign of the mural the next night. Sandy is startled to see the walls and ceiling are once again as white and plain as unmarked tombs. (He didn't have any time to repaint. He left for work before me this morning and came home long after I did this evening…)

In the glow of the beautiful light, Mazzonelli sits peacefully on his bed, piecing together large squares of material. (He must be making a quilt…)

The scraps of cloth are peculiar and irregular shapes, yet Mazzonelli fits them all together perfectly, like a jigsaw puzzle. Though at first they appear to be plain, as she scrutinizes them through the binoculars, Sandy thinks she sees designs on each piece.

(No, not designs. They're scenes.)

The longer she looks, the more clearly images seem to take shape -- crying babies, cavorting children, schoolrooms and supper tables, country lanes and city streets, churches and stores. Lovers coupling, lovers quarreling, people arriving, people departing. Births and weddings and deaths. Wars and storms and summer days, starry nights and sunny noons, gardens and graveyards. Houses full of life and light. Houses as empty and desolate as old husks.

And faces. Each different, yet somehow the same. (I recognize these…)

Faces forever captured in every action and emotion imaginable—laughing, sleeping, smiling, weeping, flushed with pleasure, pinched with pain, softened by love, hardened by despair.

Faces looking up toward the sky or down to pray or in the mirror or—(oh, my God)—watching out a window through a pair of binoculars.

Hot with humiliation, Sandy steps back, slipping deeper into the darkness of the room.

(How long has he known?)

The next night, Sandy keeps her curtains closed and watches television instead of her neighbor.

When she falls asleep, she dreams of Mazzonelli. He has his back toward her, wrapped in his patchwork quilt that shimmers like Jacob's coat. He glances around and sees her watching. He says nothing, but slowly turns to face her. Dropping the quilt, he stands, naked as a newborn and longing as a lover, silhouetted like a saint in a halo of unearthly light, beckoning to her.

All day at work, Sandy tries to decide if it was a dream or it actually happened. By the time she leaves, it doesn't matter any more.

When she gets home, she prepares herself as meticulously as she once did for the man she wanted more than her marriage, her children, her life. She showers and anoints herself with perfume, slips on a nightgown that hides nothing. When she is ready, she turns on all the lights in her bedroom, opens the curtains, and stands at the window.

(You know I’ve been watching you. My face looking out this window is a square on your quilt.)

But the quilt is gone, and Mazzonelli is busy building something. He wears a tool belt and is surrounded by stacks of cut lumber. He has his back to her, hammering pieces of wood together.

(You know I’m here. You can sense me.)

He keeps working.

(You want to meet the person behind the binoculars who judges you not.)

He nails a board into place.

Her heart pounds in unison with his hammering.

(Look at me! I’m a supernova exploding in the sky, my skin glows like a beacon in the night. I am an angel of light. You can feel my heat through your clothes like the sun on a summer day.)

He selects another piece of wood and reaches for a nail.

She raises her arms, stretches invitingly, the flimsy material of her gown clinging like skin. (Taste and see, Mazzonelli. I am a garden of delights. I am full and ripe. Take ye and eat.)

He turns to face the window, searching for something.

She extends her hands to him, palms upward in a gesture of offering. (Last night, you beckoned to me. Here I am, Mazzonelli.)

He stares in her direction for a long time, then picks up the hammer and resumes his work with the resounding finality of a slammed door.

She stares at his back, unreadable and refusing.

(I'm making a fool out of myself.)

A wail forces its way through her clenched teeth.

(…again…)

She sinks to the floor and weeps, harder than she wept when the marriage failed and the children left without a wave or a look behind, and then the man she'd given up everything to have casually announced, “I’ve met someone else...” and hung up the phone, leaving her more alone than she had ever dreamed it was possible to be.

When there are no more tears left to cry, she dries her face on her nightgown and takes a last glance across the street. Mazzonelli is standing at the window, head tilted, gazing up at the night sky, baptized by that strange light in his room, so blindingly white now that it hurts her eyes. She can't quite see what it is that he's made tonight. It looks like a big wooden rectangle in the middle of his bedroom.

(He isn't waiting for me. He's studying the stars. I might as well go to bed.)

Sandy gets up from the floor but doesn't move.

Mazzonelli is staring straight at her.

She wraps her arms around herself to hide the revealed reality of sagging breasts, excess flesh, a spent body gone to seed and foolishly showcased in a see-through gown. She can feel his eyes search to make contact with hers, she can sense the grace of a wry smile, she can hear his heartbeat as light and lifting as birdsong. Her knees go weak, she begins to shake, a gasp slips from her lips. Though she wants to run and hide, she holds out her arms in supplication to the bad man across the street.

Slowly, he bows to her—a deep, humble, knowing bow—and turns to go.

“Mazzonelli!” she cries. Her voice echoes emptily across the canyon of concrete.

But the beautiful light is suddenly extinguished, and he is gone.

No one has seen Mazzonelli for days. The neighbors think he’s run off with a 15-year-old girl—“Just like that creep, to pick up with jailbait, you know.”

They say he's gone on a bender. Left for the coast. Gotten his worthless self murdered by some lowlife in a sleazy bar on the wrong side of the tracks.

Or killed himself.

The neighbors walk slowly by his house, waiting for the telltale smell so they can have the satisfaction of calling the police about him one last time.

Night after night, Sandy waits by her window, starved for the magnificent light, for the sight of the sad little man, for another look at the last thing he created.

More than anything she has ever needed in her life, she needs to know for certain what it was he actually made that night.

Tonight, Sandy doesn’t look out the window. She makes her dinner—a real one, from scratch, like she used to long ago, in another lifetime—but this time it's turned out terribly, though. The meat is barely cooked and bloody, the rolls are burnt, the vegetables so overdone they're disgusting mush. But she knows she'll eat every bite, no matter how dreadful, and tomorrow make another meal which she suspects will undoubtedly turn out even worse. And she'll keep on doing it until one day, providentially, she will no longer need to any more.

She’s bought a bottle of good wine and a cut-crystal wine glass that glows with promise, like a diamond, and set her table with dozens of candles.

“Let there be light,” she says, as she applies a match to the many waiting wicks.

She pours the wine and lifts her glass in a toast to the man who is not there.

She understands now what Mazzonelli created on that last night.

It was a door.

©2002 by Phoebe Kate Foster