Americano: An Interview

with Emanuel Xavier

by Travis Montez

Emanuel Xavier is author of the poetry collection, Pier Queen, and the Lambda Literary Award nominated debut novel, Christ-Like. He is the recipient of a Marsha A. Gomez Cultural Heritage Award for his contributions to gay and Latino culture, and was selected as Poet Laureate of the 2002 Brooklyn Pride celebration.

Emanuel Xavier is author of the poetry collection, Pier Queen, and the Lambda Literary Award nominated debut novel, Christ-Like. He is the recipient of a Marsha A. Gomez Cultural Heritage Award for his contributions to gay and Latino culture, and was selected as Poet Laureate of the 2002 Brooklyn Pride celebration.

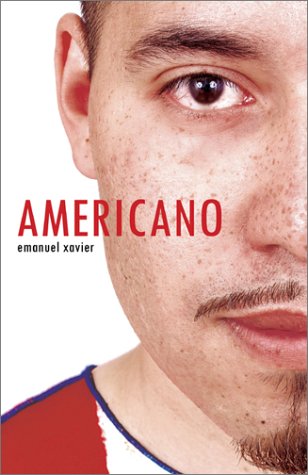

In 1996, Emanuel Xavier took the New York City spoken word scene by storm, quickly becoming one of the most significant voices to emerge from the neo-Nuyorican poetry movement. Following in the tradition of writers/performers like Miguel Pińero, Xavier captivated audiences with a fresh and poignant brand of art that celebrated sexuality, Latino heritage, and the often-brutal streets of New York. Today, six years after he first graced the stages of smoky cafes and independent theaters that made up New York's underground poetry scene, Emanuel Xavier has released his second collection of work, Americano.

A painful past of sexual abuse at the hands of an older cousin, rejection by a devoutly religious (and homophobic) mother, homelessness, and a life of prostitution and drug-dealing, are among some of the experiences that have served as inspiration for the vibrant and emotionally raw poems for which Xavier has become famous. Pier Queen, released in 1997, was Emanuel's debut anthology, which included many of the poems that earned him the Nuyorican Poet's Café Grand Slam Championship.

In 1999, Xavier released the semi-autobiographical novel Christ-Like, which garnered a Lambda Literary Award nomination. A year later, these achievements prompted Paper magazine to choose Emanuel Xavier as one of its "50 Most Beautiful People."

With Americano, the self-proclaimed Pier Queen has grown up. With thirty-five new poems, Emanuel Xavier considers what it means to be American -- but Latino; Latino -- but gay; Nuyorican -- but Ecuadorian; revolutionary -- but not an activist. In essence, Americano is the next chapter in the life of a native son surviving the contradictions of his homeland.

TM: It has been five years since the release of Pier Queen. That anthology was an intensely personal look into your life as a survivor of sexual abuse, prostitution, and drug dealing. Your first novel, Christ-Like, was released in 1999 and dealt with similar themes. Now that you are a successful writer and have seemingly come such a long way from those days on the pier, what will Americano reveal about you?

EX: I'd like to think it displays a sense of growth. Writing has become

a sort of ritual purification. As a whole, I see it as cynical, street smart,

idealistic, and indestructibly self-respecting.

TM: How did the process of writing and collecting the poems for Americano differ from that of Pier Queen?

EX: My first collection focused more on the performative aspect of poetry. I had made a name for myself at the Nuyorican Poets Café and was excited about winning several slams. In a rush to have something physical to hand over to the crowd, I self-published Pier Queen and included "filler" poems to complete the collection. Nonetheless, it found an audience somewhere between its strengths and weaknesses. I think Americano remains faithful to my past while shamelessly rising above it. The new collection is a garage sale of words ranging from the performance poetry that brought me here, to a pair of tributes inspired by a Keith Haring poem, to the collection's heartfelt reflections about my personal life since Pier Queen and Christ-Like.

TM: How have you changed as an artist since your debut anthology?

EX: I'm trying different styles of poetry and focusing more on the page rather than the stage. I could simply give my audience more of what was found in my earlier writings and risk boring them. But I chose to build on the style I had already established in an honest and creative fashion that hopefully reflects legitimate growth and maturity.

TM: Do you think the poetry/spoken word scene has changed since you self-published Pier Queen?

EX: It seems to have lost some momentum, simply because I think a lot of artists use the spoken word scene as a launching pad for other careers such as acting or music. The slam scene is a great place to start but anyone with the determination to win usually has other ambitions worth exploring. Besides, there are always fresh, inspiring, new voices worth checking out so there will always be an audience.

TM: Was there any anxiety about releasing another book?

EX: It is said that the third book is actually the most important one in a writer's career. I may generate fewer sales and less attention than other Latino writers, but I hope it sets me up as an artist for the long run. It simply comes from the heart.

TM: Many of the poems in Americano directly or symbolically detail your struggle with trying to heal from your past while enjoying the new life you have created for yourself. In one such poem, "Elegantly Fucked," you write, "Settling down was meant to end my prostitution/but poetry will always keep me on the streets." Can you elaborate on what this means?

EX: There are still those people that, no matter what I do, will always think of me as a prostitute. Unfortunately, my past always precedes me and people always have certain expectations. Recreating myself as a poet hasn't necessarily made my life better. In going after what I wanted, other things fell by the wayside, things I should have maybe paid more attention to.

TM: As the title suggests, many of the works in this collection deal with issues of race and culture. What does it mean to be Americano?

TM: As the title suggests, many of the works in this collection deal with issues of race and culture. What does it mean to be Americano?

EX: I actually wrote the title poem for anyone, specifically Latinos born in this country, without white skin, blonde hair, and blue eyes, who never got a piece of the American pie. Then September 11th happened and everybody woke up to the fact that this country was made up of so many different people from diverse backgrounds. However, the poem still has resonance because America at large needs to be reminded that being born in this country gives you the right to be part of its dream. It shouldn't take another horrible tragedy to bring back that unifying experience.

TM: The first poem in this collection, "Wars and Rumors of Wars," touches on everything from your response to September 11th and the current scandal with the Catholic church to Columbine and homophobic violence. Though you are critical of intolerance, in this poem you appear to be somewhat self-conscious about your role as a poet/activist and revolutionary.

EX: I do not consider myself a gay activist. I write from the heart

and express things through poetry and literature. If my work happens to be political,

and much of it is, I welcome anyone who identifies with it on that level. However,

I can only contribute to my culture through my art, which is what I know best.

I can't write to suit a particular group or organization. I support them wholeheartedly

and thank them for their support, but I just want to create without binding

myself to any group. It is important for any artist to be a free-spirit and

make their own decisions about how to express themselves. Limitations do not

work well in art. Ironically, I have given voice to a group that has been silent

for too long and brought them to light with my writings.

TM: In several poems you are remarkably candid about the domestic violence your mother suffered ("Magdalena") and your own experience with violence at the hands of your partner ("Love Remembered"). Violence within gay relationships is such an overlooked and taboo issue, was it difficult for you to be honest and open regarding this subject?

EX: It was something incredibly close to me and very painful. I had a difficult time writing about it. It wasn't like my ex physically abused me on a regular basis. It only happened once and it was over. I watched my mother and stepfather survive a destructive relationship that seemed powerful and futile. In the end, I suppose that experience made me stronger because I realized I would never want to continue a terrible relationship and allow myself to be victimized that way.

TM: The most amazing achievement of Americano is your ability to make "revolution" personal. When most people hear that word, they think of armies and tanks invading some small village or Communism. However, you evoke the image of revolution in poems about buying your white boyfriend's niece a Latina Barbie doll ("Teresa") and Tito Puente's legacy ("It Rained the Day Tito Puente Died"). What is your revolution? What change are you attempting to make with your work?

EX: I would like to think that I'm giving voice to a part of our culture

that has been greatly overlooked in gay literature. There have been many great

gay and lesbian Latino/a writers before me that have shared their own personal

experiences and brought attention to a particular group. For example, Reinaldo

Arenas giving voice to gay Cubanos, and Jaime Manrique writing about his experiences

as a gay Colombian living in Times Square. There have been many gay Chicano/a

writers that have contributed so much to our revolution…one of my favorites

being Sandra Cisneros. I write about the gay Nuyorican experience because it

is what I know, and somewhere along the line I also represent the gay Ecuadorian

community because of the mix in my blood. In itself, these are two very different

cultures, which become blended with the New York experience because it is my

life, my history.

TM: As an artist, what did you get out of the experience of writing this latest collection?

EX: When I first started this collection, I had hoped for a different tone from all of my previous work. I learned that a lot of my writing is still driven by angst; I'm simply pissed off about different things these days. It's probably not as clean and accessible as other poetry. But then, I realized I was never concerned with poetic integrity as much as creative freedom.

TM: What do you hope your readers will take away from Americano?

EX: I hope they can read between the lines and realize that I was only able to appreciate survival after taking a road toward self-destruction. I am still a scared little boy inside who needs attention, and like most, contradiction of your own true self is sometimes the only way possible to become aware of who you are and what you want in life.

Read a poem, Born This Way, from Emanuel Xavier also in this issue

Emanuel Xavier is author of the poetry collection,

Emanuel Xavier is author of the poetry collection,