Adrienne Ross

Walking in Nepal

Leaving Chomrong, the trail into the Annapurna Sanctuary followed the top of a five-foot high wall. My legs hardened like the stone beneath me. Panic tingled up my spine. I forced myself to breathe. Take a step. Another step. Another. Before I came to Nepal, I never could have walked that high above ground. There, I had to. I couldn't change my mind. I couldn't turn back and wait for people in the parking lot. It was why I went to Nepal 12 years ago.

Being afraid of heights had always been a fact of life. I had brown hair. I weighed 137 pounds. I had a temper. I was afraid of heights. I knew the leg-tingling terror of looking down. The nausea of standing on an edge, any edge. Giving up. Going back. Worse, standing at forest edges and mountain passes, beautiful places I longed to wander through, stopped by a border of fear I couldn't cross. I didn't have a fear of heights. My fear of heights had me.

Fear whispered into my ear during the 36-hour flight from Seattle to Bangkok, the flight into Kathmandu, the flight over the Himalayas to Pokhara, the bus ride to a field outside a Tibetan refugee camp where the three week trek would begin with a group of women strangers and Sherpa porters. From the Hotel Dhampus to Landruk, I froze on mud, forgetting to keep my weight low and over my legs. I grabbed for twigs and bramble, my legs rigid between hesitant steps. Across the mountains from Landruk, I heard bells echoing off pony caravans coming down the slopes, the ringing warnings of impermanence perishing into the bright mornings, the noon suns, the twilights of exhaustion after gaining 2,000 feet, 2,500 feet, 3,000 feet after walking all day, two days, three days, five days. From Landruk to Ghandruk I walked along trails that took me to roadside bhottiyas (tea houses) where trekkers sipped hot lemon tea or coca-cola, and postcards of Miami Beach and the Eiffel Tower were pushed into chicken wire-covered windows. On the way to Chomrong, I walked past houses strung with marigold banners, up trails that turned to corkscrew paths of gold dirt and loose stones, across suspension bridges of rusty metal cords and wood planks that werenít nailed down, through bamboo forests or up stone steps worn near to dust. I kept my eyes ahead, my vision narrow. My legs were rocks trembling with exhaustion. My toes were shrouded in moleskin. Sweat and sunscreen streaked my face. I walked on, having no choice, putting one foot in front of another, up passes so high I looked down on Bonnelliís eagles flying above mountains and distant roads. Always the white tips of the Himalayas gleamed above the clouds. I knew only the hesitancy of my steps, the feeling of being pulled backward, the habit of fear.

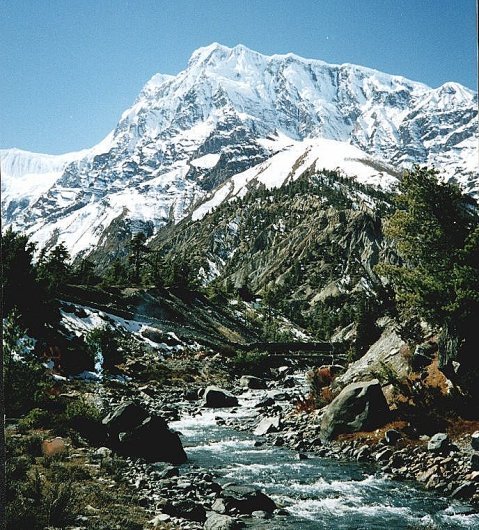

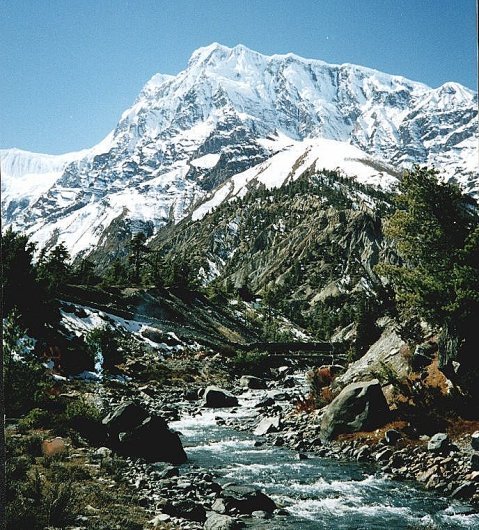

Out of Chomrong was a hard, hot trail of blood-red dirt, bhottiyas and rock outcrops. From a long way off, I could hear a river rushing, goats rustling in the grass, dogs barking in the valley below. I went down through forests where the slopes could be two feet or two thousand feet. I went up boulders worn to 45 degree sides by so many foreign feet. Down a narrow trail of steps broken into loose rock and stubs of toeholds. Up footholds of tree roots. Which rock was loose? Which clump of leaves covered mud? Which step was right? Which step was wrong ? At home, I never walked a trail past where I couldn't see it curve. As long as my steps stopped, the future was known. Possibilities were manageable, because they didn't exist.

Flies zoomed around my nose as I halted, stepped, negotiated this unknown future of mud and rock. As the days and miles passed under my feet, I learned to lower my weight, relax my vision to decipher mazes of tree roots and boulders, numb my spirit while keeping my legs moving. I turned away help from outstretched hands as often as I could. Otherwise I would never learn to hold my breath, clamp my jaw, and constrict my heart until I didnít feel my terror. Which step? Just get down. Just get up.

Butt first and backwards, I shoved myself up vertical boulders that caught my pack. A turquoise sky gleamed through the swaying bamboo. A barefoot porter with an aluminum table strapped to his back went down in nimble steps, never once breaking stride.

The trail became a world of waterfalls. Streams of shadows and illumination wove through the bamboo forest; rivulets caught in shallow pools, trapping gold leaves and reflections of clouds that scattered with my steps. Porters stopped to cook dal bhat by a waterfall. I kept walking, as I had for hours, all day, several days, too tired to know myself or where I was. Each step brought another fear: did I have the right to do this if I wasnít as good as the others? Shouldnít I be as fast as the others? Shouldnít I be stronger? Shouldnít I never need help? Each step was the start of a journey past the lies of who I was supposed to be. A barren yet fruitful honesty was taking root. I could only be who I was: a woman who hiked neither fast nor slow; who breathed deeply and painfully the higher we gained altitude, who came to camp too tired for backgammon games. A terra incognito of questions, grudgingly navigated, that would over the years become home.

The hollow-sounding swaying of bamboo became the call of the late afternoon wind. Far below me I heard a river lost in the thick woods. The mountainside across the river sheltered a shooting star of a waterfall that had broken free of the forest to become enshrouded by the rising fog. The sky was leaving. The white world above me remained, and the water of another mountain stream that flowed over my feet.

Eight hours of hiking that day. Only five hours to Machupuchare Base Camp.

Annapurna Approach Lodge to the Machupuchare Base Camp

I woke in a damp sleeping bag, thin layers of ice lining the tent's walls. Our head Sherpa was unwilling to say how long we would be in the sanctuary or what the weather would be like. Normally the trek would have spent more time at 9,000 and 10,000 feet, wandering through villages and learning to walk at high altitudes. We had hurried before rumors of storms and hard winds.

It was hard to remember the days. How far had I walked through lands where I didn't know a dozen words of what people were saying? How long had I been away from home? I wore a watch, although there was no time I had to be anywhere. Get to the lunch site before the dal bhat, or chapati with jack cheese was gone. Get to camp before dark and wait for an overworked Sherpa to arrive with my duffle. Eat dal bhat, or momos, or macaroni with carrots, or potatoes and ramen soup. Go to bed before dark. Sleep. Eat meusli for breakfast, maybe an egg. Start walking. What I remembered was not time but place: rain falling on my bathroom skylight at home; hot water on my shoulders, strawberry soap bubbling over my stomach.

Yet how comfortable I felt. I had not looked in a mirror in over a week. For the first time my body had a function. I no longer considered myself in terms of my beauty or sexuality; the rounding fat on my hips, the stretch marks on my breasts. Everything was a matter of strength. How long could I walk? How deep was my breathing? How firm were my quads? My body had a purpose: get me somewhere down the trail; carry me in and out, all by my strength. I had become my short-cropped brown hair and sun-chapped lips; the sweet bitter rot in my armpits; the dusky scent of old urine and musk when I opened my legs to take another step.

We hiked along a rocky, uphill trail sheltered by low-hanging bamboo. Waterfalls were shrouded in ferns. Skeleton fingers of water moved over the moss-covered mountainside, grasped the brown husks of what were once wildflowers, then slipped across the trail and over my mud-gray hiking boots, before joining the river at the mountain's base. Froth caught in pools far below me, swirled in white circles between boulders scoured to silver and gray, rushed down between the rocks.

I crawled hand and knees over loose rock, boulders, red dirt, past wild strawberries, across the dry streambed where a waterfall once flowed from the summit to the river far below. Now it was a sea of red dirt I didnít know how to cross or climb. If I saw how high I was I would be scared. I was careful to see only the next toehold.

Suddenly I was in the light. The forest was gone. In its place was a vista of rock and grasses dried yellow and red in the sun. Cloud tendrils were caught in mountains of snow and red earth, wisps breaking free for the blue sky between the peaks. I spat up yellow mucus, swallowed my snot, breathed the short, rapid pants that made me lose my breath before I gained it. Hiking this was not a nightmare as much as a wearisome dream happening night after night, always waking up before it ended. Barefoot women porters in dirt-dark lugis (skirts) labored past me, crates and dolpos (woven baskets) strapped to their necks and backs.

A bridge of narrow logs straddled a river rushing with the thaw. Loose rocks, coated with ice from the freezing splashes of river, were the only wobbly footholds in the gaping inches between the logs. A group of Australian trekkers on the other side saw me unable to walk a step or two or three to meet their outstretched hands. I let a trekker pass, then another. It didn't matter that I knew I couldn't do it. This high, this far from home, all I could do was cross it. But I couldnít. I took off my rucksack and tried to crawl across the river rocks. The air was cold with the wind traveling down the rushing water. One of the Sherpas with our group turned the trail to see me and rushed forward, grabbing my hand and leading me over the bridge. I was too numb to feel embarrassment or the gratitude the porter deserved.

Safe on the other side, heart pounding and legs trembling, I watched people cross the bridge. Some of the women were helped, some crossed it on their own. I remembered that what I felt beneath the fear was an assumption hard and dry as the rocks around me. I couldnít do it. Find another way. My fear created an illusion of a false safety in crawling over icy rocks above fast, freezing water. Crossing the bridge was a humiliating but needed reminder in taking the seemingly dangerous but safer route of risking movement, taking small step after small step, accepting help when needed.

Vertical rock and a dirt trail no wider than my hand snaked up the mountain side. We were at 10,000 feet in altitude, or higher. One hundred or one thousand or several thousand feet below was a river. I didn't look up. I didn't look down. I didn't wonder if it would help if I cried. I watched the trail when it existed and tried to make a new one when it disappeared. A pins and needles headache rose up the higher I trudged.

Where there should have been waterfalls were veins of snow and ice bleeding down the mountainside. The valley narrowed the higher we went. Two thousand more feet before reaching the Machupuchare Base Camp. Three more hours at my pace. The wind blew my shadow ahead of me. I followed. Past the dried red berries on thorn bushes. Past the echoes of avalanches. Past shrub bushes silver with frost in the afternoon sun. I pulled up the sleeve of my polypro shirt, and an orange butterfly took to sparkling flight. How long had I walked with it sheltered in the folds of my sweat soaked shirt? I followed the curving trail to a stand of barren, wind-twisted trees, snow scattered in heaps about their roots.

A slow, constant walking in and out of nightmares, without strength in my pounding heart, only stubbornness. The fog blew past in ominous wisps. My ears were numb. Headaches exploded in my skull. At the next ridge was a cluster of stone buildings. Once there, I followed the trail down a shrunken, half-frozen river, only to trudge upwards to join people huddled by a stone wall far above me. Tibetan ravens circled as they flew through the fog that flooded the valley.

I wanted to sit amidst the brittle gold stalks of what was once a flower, rest my stinging feet on the rigid mud, trust that the fog would bring a mirage of an end. I longed for a place of my own with that fierce irrational trust that the world could not be as cold and uncaring as it obviously was.

I went down across another river walkway of logs weighted down with loose rocks, up a foot-carved staircase in the frozen earth. As if I was walking through bardo, the dangerous, unsettling time that Tibetan Buddhists believe exists after death and before rebirth. I was too far past strength or stubbornness to know if I was leaving one life for another. I knew a cold too deep for words, too pervasive to be felt. I knew the calls of ravens, fog that circled my feet, short, stabbing pains as I gasped for breath. Step. Two steps. Step again. Step. Step. I looked behind me. Was I the last? The Sherpa who had helped me at the river was now leading another woman. She was lost beyond exhaustion, knowing only she had to move, trusting that somehow she would, not knowing where or why. Ice-veined earth crunched under my steps.

At the top of the slope one of the Sherpas waved to me. I bowed. I saw the tents. I was at the Machupuchare Base Camp, 12,000 and many odd feet higher than I had ever been in my life. We gathered inside one of the tents, ate M&Mís and candy corn, told stories my ears were too numb to hear. My head throbbed with pain. We sang to the last person to arrive. I started to cry.

Machupuachare Base Camp

Bone cold winds. Insomnia my first night at the base camp. Nausea at breakfast while forcing myself to chew museli, sip tea. Hours spent burrowed into my mummy bag. Too cold to sleep. Too tired to write. Finally I roused myself to trudge to the bhottiya for a cup of hot lemon tea and ramen soup.

Near the bhottiya a footpath snaked its way to a hilltop. Didnít I know what I would see there? Another view of endless mountains, unending sky? It was a steep path, and I walked not from the ruthless necessity of the past weeks, but from curiosity, a wayward angelís prod, another turn of my karmic wheel. Soon I was crabwalking on my butt, gloved hands gripping grass and frozen ground, terror rising with me as I reached the top. Inches from me the hill dropped to a steep gorge where a river too far away to be heard coursed through a boulder field. Were I to fall, the rushing water would carry away my body for miles, never to be found.

For a minute, or two, or ten, I sat looking down in exhausted awe at a landscape I could never have imagined, even after the past few weeks. I sat alongside my fear, neither running from it nor into it, neither conquering it nor immobile before it. A truce.

Snow was falling with the fog coming down from the mountains. In the lodge below were voices in French, German, English; men with dark stubble, women with hair hanging in dirty clumps, all turning tired eyes and grimy fingers to maps, journals, letters home. The same weariness of moving forward only to arrive in a barren, unknown place was in me. Slowly I navigated my way down to level ground. I had thought the trip a failure: my fear was as immovable as the mountains. I did not understand that what had changed was that I was learning to no longer be afraid of my fear. A whisper of the years ahead, where more and more, fear would become a feeling like love or joy or any other, no longer an implacable barrier. I did not know that the dying in my mind, the slow coldness without air to breathe, the food that was warm and soft and tasted like nothing, the shadows on the faces I saw, the darkness on my hands, was not simply sickness from having come too high, but what the Buddhists call prajnaparamita, an emptiness of the fullest possibilities. The great mother: the blank page before I wrote on it; the snow gleaming deep within mountain furrows.

There would be difficult days ahead of descending mountain passes, walking alongside temples and under monkeys in the trees. I didnít know that the journey would continue in the months and years to come. Fear was a tapestry, each thread weaving into another. Pull one, and they all unravel. No longer would I take jobs from necessity, believing I couldnít find work I wanted. No longer would I put off writing until sure of the perfect piece. I had learned to risk, to walk farther and higher past fear into new vistas, into unknown and hopeful futures.

©2003 by Adrienne Ross