Ed Markowski

One of Us

My wife was playing roulette. Our friends, Steve and

Anna,

were somewhere in the room trying to beat the house,

on

a rainy night at the Leelanau Sands Casino.

I was sitting at the bar listening to an old woman

explain

the finer points of blackjack when I noticed him

windmill

past the wheel of fortune. He was wearing grey

pinstripe

shorts and a matching baseball jersey. His white

sneakers

were dotted with mud from the casino parking lot.

Standing next to the old woman, he ordered a beer

and a

bag of potato chips. I thought I recognized him, but

he

looked the way all of us looked during the demise of

Nixon

and the dawn of Carter. He twisted the cap off the

beer,

tucked the chips in his back pocket, and vanished

back

into the smoky room.

Midway through another Molson, Anna walked up to the

bar

holding a quart sized cup filled with coins. "I hit

the lucky devil for eight-hundred quarters, and

Steve wants you at

the poker table, he said it's an emergency."

When I found the poker table, a red vest was raking

Steve's

bet across the green felt. "You know who that guy is

shoot-

ing craps over there?" Steve asked, pointing to the

baseball

jersey I'd seen at the bar.

"I saw him twenty minutes ago, and I thought he

looked

familiar."

Glancing at the man again, I noticed he was talking

to the

dice as he wound up to throw them. Right then, I knew.

That summer at our house in Ann Arbor had seemed

endless: great films, poetry, beautiful girls, and

baseball.

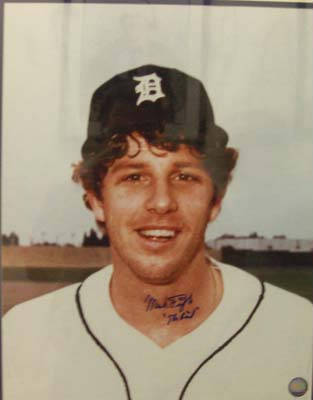

When Mark Fidrych, aka "The Bird," pitched, the porch was packed.

We watched him make his national television debut on

a Philco black and white, in box seats that John had

found in a tunnel at the stadium.

We expected him to pull rabbits out of his hat, and

he did.

He beat the Yankees that night with a slider that

broke the

wrists of every hitter.

We watched every game he pitched. It was so easy to

envision one of us, one of the guys on the porch,

standing

out there on the mound in Tiger Stadium.

Even though that summer seemed endless, we knew time

was flying, because our baseball heroes weren't our

grand-fathers or fathers anymore. They were us.

At the end of that glorious bicentennial season, he

was

19 and 9. Rookie of the year. Just one of the long-haired guys drinking a beer on the porch in Ann

Arbor.

In July of 1977, I was driving to a writing seminar

in Boulder,

Colorado. Just outside of Ottumwa, Iowa, I picked up

WJR

from Detroit on the car radio. Ernie Harwell's voice, dim but

clear in the cornsilk sunset, said, "Houk took him out

in the fourth...a recurrence of the shoulder injury he

suffered...after he hurt his knee in spring training."

The next morning in Central City, Nebraska, I bought

a Rocky Mountain News from a paper box on a dusty

street corner. On page five of the sports section

there were three

brief lines describing his shoulder injury. And,

that was his

career.

Now, twenty years -- almost to the day -- after the

shoulder

injury, I was standing behind him at a craps table

in Northern Michigan. I tapped that shoulder.

"I just want to thank you for '76."

He turned abruptly and smiled. "Why man? We were

lousy

that year. We didn't win many games."

My wife walked up, and I introduced her. He pumped

her

hand the way he used to pump the hands of his

infielders

when they made a play.

"Why'd you marry this guy?

he asked her. "He actually paid money to

watch the '76 Tigers play." Then he turned to me

and

laughed, "Come on, why'd you like that team?"

"Because, you guys were fun. A hippie pitcher, and a

convict in centerfield. It's hard to explain, but

you were just one of us."

"I still am," he answered. "The only difference is that I had a whole year

in the sun, and most people don't get a minute. Hey man,

I got to be Dizzy Dean for a whole summer. You know,

I beat the odds once in my life."

The roll came back to him. He shook the dice in his right

hand and shouted, "Seven baby, come on, gimme a

seven!" A four came up.

©2004 by Ed Markowski