Suzanne Nielsen

The Wonderful World of Machiko Hasegawa

"I'm not even going to attempt to talk about Japanese comics, but I will bring in a manga expert to talk with you during the semester," I said on the first night our Graphic Novel class met the summer of 2005 at Metro State. It's not that I had dismissed the Japanese art form of comics, referred to as manga, entirely; it's just that I had not read any to date, and knew I was out of my element in attempting to talk about the billion dollar industry in Japan, where the average reader covers 16 pages of manga comics in a minute. Give me Spiegelman, Pekar, or Eisner, and I could talk for hours. Scott McCloud's great text, Understanding Comics, is my Bible; it offers me the greatest source for inspiration and encouragement when working on my own comics.

After the class was over for the semester, however, I knew it was time to educate myself with manga comics, so I started to read several series put out by Tokyo Pop. Starting at the back of the book seemed unusual, but I quickly got used to that. Panel-to-panel transitions were formatted differently than what I was used to in western-written comics, but that too was an easy adjustment. What I also observed is what McCloud mentioned in Understanding Comics -- there's a distinction between Japanese comics and western comics even more significant, and it is this: because we are a culture that is so goal-orientated, we focus on "getting there," whereas in manga the focus is on "being there." As a result, McCloud states, "In Japan, more than anywhere else, comics is an art of intervals."

Ah, yes, what is left out is an art all of its own. The careful omitting and selecting of art and text in comics is an endeavor that many of our superheroes fight against. The end result: Gotham + Sin City = Shaun of the Dead. What the hell happened to a slice of life?

Let me introduce you to Ms. Sazae, alias Machiko Hasegawa. Just as Charles Schulz created Charlie Brown and Peanuts, Hasegawa birthed a 27-year-old female in 1946 who, three years later, would landscape the Asahi Shimbun newspaper from 1949 to 1974, through a four-panel daily comic strip,"Sazae-san." Sazae Isono, the insistent protagonist, was an active feminist, and involved in the women's movement during her twenty-eight year run with the major paper. Her three years previous were spent in limited print editions of smaller newspapers, where Sazae was initially single. Although she remained ageless throughout her lifetime, certain events in her life did change from her first inception; she did end up marrying, surprising her mother, who thought Sazae was too much of a tomboy to ever attract a husband. The strip branched over three generations, including Sazae's parents, their two younger children, Sazae, her husband, and their child. Its brilliance as a successful strip is associated with the fact that the comic dealt with ordinary issues, hence the readers could relate to it in post-war life. In the introductory article in the Asahi Shimbun newspaper, Sazae-san introduced herself: "Some of you may have heard of me. I'm a young, housewife living in town, and, being a bit scatterbrained, I provoke quite a lot of smiles among my neighbors. My husband is Masuo Fuguta, and our small son is Tarao (though we call him Tara). Housing is a problem for us, just like everyone else, so we are living together with my family, the Isonos. As well as my father and mother, there is my naughty brother Katsuo, and my sister Wakame, who is six, making us a big family of seven people in all. I hope you enjoy the sort of funny things that happen in this lively family."

I was lucky enough to find twelve used volumes of The Wonderful World of Sazae-san, at Half-Price Books over the last several months, which were translated by Jules and Dominic Young. Since more than 62 million copies of the comic book sold in book form, I guess Blaine, Minnesota, can end up storing a dozen or so already read and waiting to be resold. The most endearing quality of the books is how forthcoming Sazae is with everyone around her. She insists on being in control of everyone, regardless of her better judgment at times, and in the end, it doesn't really matter, because nothing that occurred was as important as life or death. Sazae reminds us to not take ourselves too seriously, to not take life so seriously that we end up creating worlds of superheroes battling each other for the need of "getting there," versus "letting go" and "being there."

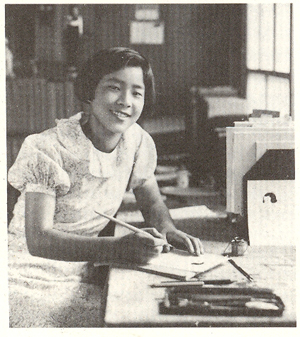

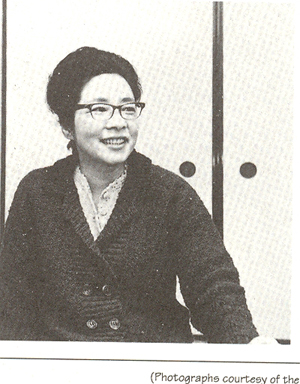

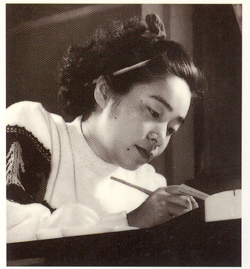

Hasegawa started drawing at the very young age of two years old. At sixteen, she began her first important apprenticeship to the cartoonist, Suiho Tagawa. Her creation of Sazae-san endeared her to become Japan's first successful woman comic-strip author. The strip went on to be adapted to an animated television series and full-length movies. There were also numerous radio shows created from the strip.

Hasegawa started drawing at the very young age of two years old. At sixteen, she began her first important apprenticeship to the cartoonist, Suiho Tagawa. Her creation of Sazae-san endeared her to become Japan's first successful woman comic-strip author. The strip went on to be adapted to an animated television series and full-length movies. There were also numerous radio shows created from the strip.

Hasegawa remained single in her personal life, even though her protagonist married. She continued to draw the strip, and breathed life into Sazae and friends until February 21, 1974, when the strip ended with its 6,477th publication. In 1985, Hasegawa opened her own art gallery and exhibited her original works. She continued working in publicizing Sazae-san as it was adapted into other mediums. In 1992, on May 27, Hasegawa died, at 72 years of age. For 50 years Sazae-san had remained Japan's best-loved comic strip, and Hasegawa was awarded a posthumous prize on July 28, 1992, by the Prime Minister of Japan. Saze-san was posthumously recognized as getting there, while being there with her through all her adventures was really the portentous feat.

Why do you think Sazae-san remains so loved, reinvented through adaptations on screen, radio, and anthologies? Why do people continue to visit the Hasegawa Machiko Museum? Because there is a connection between art, artist, and reader that must not be lost. Or, as McCloud says, "Comics offer tremendous resources to all writers and artists: faithfulness, control, a chance to be heard far and wide without fear of compromise...and all that's needed is the desire to be heard, the will to learn and the ability to see". Hasegawa delivered a balancing act through "an art as subtractive as it is additive," and we connect across cultures because her stories resonate an ordinary life that most of us have lived through western influence, eastern influence, and through the influence of generations of time.

Why do you think Sazae-san remains so loved, reinvented through adaptations on screen, radio, and anthologies? Why do people continue to visit the Hasegawa Machiko Museum? Because there is a connection between art, artist, and reader that must not be lost. Or, as McCloud says, "Comics offer tremendous resources to all writers and artists: faithfulness, control, a chance to be heard far and wide without fear of compromise...and all that's needed is the desire to be heard, the will to learn and the ability to see". Hasegawa delivered a balancing act through "an art as subtractive as it is additive," and we connect across cultures because her stories resonate an ordinary life that most of us have lived through western influence, eastern influence, and through the influence of generations of time.

Carly Berwick, in her recent article, "Why Have There Been No Great Women Comic-Book Artists?" (artnewsonline, November, 2005), reminds us that here in our western culture we have a recent honoring of comic artists in an exhibit that opened in November 2005, titled "Masters of American Comics," in Los Angeles. The show ran through March 2006, and hosted some of our beloved masters, including Spiegelman and Schulz, but there happens to be one overlook: among the masters included, no women appear. "There are no women in the show," quotes Berwick. Why? According to the show's curator, the "selections were based on the criteria of craft and formal innovation." As far as I can figure, that would include over a dozen women comic artists I can think of without going to my sources.

Trina Robbins, a wildly delightful and gifted comic artist and feminist (most likely friend and soulmate of Sazae-san and Machiko Hasegawa), states that one reason women are overlooked among the masters is "because of the prevailing esthetic mindset that values explosive drawing." This brings us back to the "getting there" vs. "being there" concept, and the superheroes fight to overpower, to control, to rule. Sound familiar to our system of government? Interesting to note that none of our masters (presidents of the US) to date have been women. Do you think it's due to "selections based on the criteria of craft and formal innovation?" If we take a look at the "powers that be" now, would you say there is a "prevailing esthetic mindset that values explosive drawing," in our newspapers, our government, our "democracy?"

Ah, yes, shame on me for dismissing manga. Shame on me for honoring the masters of male dominance in a graphic novel class, even though I profess to be a feminist. Sazae-san has some work to do in teaching me, through her several volumes, and I in turn have some work to do in teaching others about the true masters of comics. You now know about one: Machiko Hasegawa.

©2006 by Suzanne Nielsen

Hasegawa started drawing at the very young age of two years old. At sixteen, she began her first important apprenticeship to the cartoonist, Suiho Tagawa. Her creation of Sazae-san endeared her to become Japan's first successful woman comic-strip author. The strip went on to be adapted to an animated television series and full-length movies. There were also numerous radio shows created from the strip.

Hasegawa started drawing at the very young age of two years old. At sixteen, she began her first important apprenticeship to the cartoonist, Suiho Tagawa. Her creation of Sazae-san endeared her to become Japan's first successful woman comic-strip author. The strip went on to be adapted to an animated television series and full-length movies. There were also numerous radio shows created from the strip.

Why do you think Sazae-san remains so loved, reinvented through adaptations on screen, radio, and anthologies? Why do people continue to visit the Hasegawa Machiko Museum? Because there is a connection between art, artist, and reader that must not be lost. Or, as McCloud says, "Comics offer tremendous resources to all writers and artists: faithfulness, control, a chance to be heard far and wide without fear of compromise...and all that's needed is the desire to be heard, the will to learn and the ability to see". Hasegawa delivered a balancing act through "an art as subtractive as it is additive," and we connect across cultures because her stories resonate an ordinary life that most of us have lived through western influence, eastern influence, and through the influence of generations of time.

Why do you think Sazae-san remains so loved, reinvented through adaptations on screen, radio, and anthologies? Why do people continue to visit the Hasegawa Machiko Museum? Because there is a connection between art, artist, and reader that must not be lost. Or, as McCloud says, "Comics offer tremendous resources to all writers and artists: faithfulness, control, a chance to be heard far and wide without fear of compromise...and all that's needed is the desire to be heard, the will to learn and the ability to see". Hasegawa delivered a balancing act through "an art as subtractive as it is additive," and we connect across cultures because her stories resonate an ordinary life that most of us have lived through western influence, eastern influence, and through the influence of generations of time.