Dean Ballard

Unveiling The Fidrych Card

At the Asphalt Trucking Company in Massachusetts does Mark Fidrych enjoy any peace in his heart today? It was a torn cartilage that led “The Bird” to his destiny there instead of Cooperstown, and I have always wondered, all these years, how anyone could live soundly after just missing immortality like that.

But who among us can lay claim to striking out Chris Chambliss or Reggie Jackson or Rod Carew or George Brett in their prime? That young man could. He knew what he was doing out there on the mound at Michigan and Trumbull, and possessed such talent, if only for a brief moment in time, to catapult himself from pumping gas in Northborough to All-Stardom and the cover of Rolling Stone magazine.

“Let me have it again,” he shouted at his catcher, Bruce Kimm.

“Bulls-eye!” yells out the great Harwell on WJR Radio during a fun afternoon at the stadium, “A called third strike!”

After the game, Johnny, Scott, and I walked from my house up to

Kresge’s store on the corner of Elkhart and Kelly Road for our daily

dose of candy and baseball cards. That’s when I heard crazy old Connie the Bum

yelling out from his back-alley. “For he whose talent shines,

a world that’s yours awaits, take it and fear no shadows,” he shouts

madly into his hand-held radio as 54,226 watch, wail, and ululate

and ultimately drown him out. He then continues teary-eyed as he spots us,

with, “My whole life feels like a fifth-place finish in September, with

frequent grounders to the left side, scents of grape Bubble Yum in the air...”

I think it was the patting-of-the-mound-with-hand and the talking-to-the-ball antics of the eternal rookie, at one with his infielders and the possessed Little Leaguers crowding around my television in our living room watching. That’s what drove Connie to his wits end, asking God under his breath if an unfulfilled dream is a lie or, in fact, something worse. “If I could have been chosen. If ONLY I could have been chosen,” he wept into an empty beer can smashed lovelessly into his old forehead, “all could be said and done and like this I’d roam,” imitating the post World War II arrogant American walk, “to a sanctum of feel and doubtless vision (here’s where his poetry got real bad) happy in time for healing and love and with a star-twinkling death…” nonsensically he muttered, once again ripped apart by life as we pass him to enter the store’s backdoor. When we step out with paper bags filled with liquorish, and Bubble Yum, and of course, innumerable packs of Topps baseball cards, he stumbles over, sits next to me on the curb and whispers sarcastically into my ear, “‘What happened to all my friends?’ you’ll ask yourself. ‘I dunno,’ you’ll answer, fretting over the nothingness and gloom you’ve found.”

Ignoring him, I ask Johnny and Scott, “Did you hear my brother got the Fidrych card?”

Connie moans in despair. I do my best to pay him no attention.

“What?!” yelled out Scotty from the bottom of his little-boy soul.

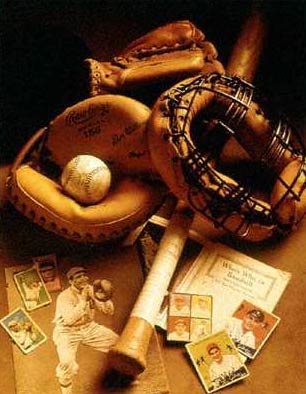

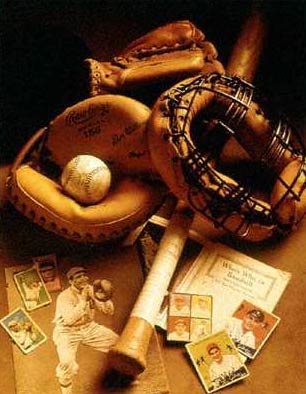

“He did, I can’t believe it,” and how I remember seeing his 1977 Topps card with that incandescent-red All-Star line across the bottom and his Rookie-Of-The-Year trophy in the lower right hand corner, a photo of The Bird smiling right at you, from one soul to another, wonderstruck by his own newly acquired fame, long curly dishwater-blonde hair that smelled of the streets of this town under his Tigers cap. The card depicted a young star-struck Fidrych. He had just met his father’s favorite singer, Frank Sinatra,

and a few days later met his own favorite, Bon Scott from AC/DC. Their latest album, “High Voltage,” released earlier in his rookie year, was a mainstay on his apartment stereo.

“When can we see?” asked Scott.

“Hold on, lets go into the store one more time. Maybe one of us can get one?” – Poor boy me, even then a fatalistic optimist.

First thing we do every time we enter Kresge’s is check out the comic book stand. On the tall rack I see the shinny new cover of Iron Man, Spider-Man, The Avengers, and The Almighty Thor. With great artwork and stories, you found a true escapist’s paradise in those Marvel and D.C. comics. We then walk to the cashier and grab our trading card packs. Paid twenty-five cents each, then went around back, sat down on the parking lot curb and furiously started to unwrap the cards. Connie The Bum noticed our return. He sat down next to me again and whispered, “Only a true heart has the capacity to break, but shall it ever mend?” I turned to him with squinted eyes, a little annoyed by this crazy old man following me around everywhere, looking like he wants to tell me something but can’t bare to spit it out so I let him be.

In my packs, I had in all, two great All-Stars: a Jim Palmer and a Vida Blue, along with a Tom Veryzer, (always exciting to unwrap your baseball card pack to find a Tiger in there, even if he’s only a .215 hitter) and a Lee Mazilli. Johnny found a Dave Parker in one of his, along with a Bill Buckner and a Jose Cruz. But Scott, this time around, even lit up Connie’s old tired eyes with four different All-Stars: a Randy Jones, a Pete Rose, a George Foster, and a Greg Nettles. All four cards had that incredible All-Star line across the bottom. Though I stood as the only one to get a Tiger, it was Scott who had the best cards on this day.

But no other baseball card was worth more to us than the Fidrych card. It was by far the most sought after pearl of 1977. My brother Pete guarded it with his life.

As we sat behind Kresge’s store a little while longer, looking over the stats on the back of each card, chewing our Bubble Yum, we talked about the Fidrych card and the millions it would be worth someday. We figured that Pete was set for life now. Our over-excited conversation caught the ears of local conman Paul Moloci, and his street smart sidekick J.P. Singlyn. Moloci was a sly-looking fast talker with an ear for The Beatles and an eye on your Monopoly money, always finding a way to cheat at Battleship as well. J.P. was his partner in crime, the quick throwing third baseman, a tough-as-nails kid whose parents kept him up all night with their reckless arguing and moonlighting till the dawn - always a house of hearts on fire, that Singlyn home.

Paul Moloci heard something about the Fidrych card and immediately an angle was crafted. “You say something about a Fidrych card?”

“No we didn’t say nothing,” stood up Johnny.

“Sit down asshole,” barks Moloci. Neither one was afraid. All this happening while the bum weeps against my arm as if we’re blood-brothers reeling through the same ominous imperfections of one life wherein I wished to be a base-steeling threat like Ron LeFlore but had no speed; a cool hillbilly cat like Elvis but had no voice; I wanted to swoon Jill Worthman and Sissy Kotek on Elkhart but had no confidence; I wanted to be an Eagle Scott standing next to the flag in my post-Harper Woods gymnasium but had no skill, always remembering what my father told me about speed – how it can’t be taught, and the finality of that!

Now it’s five of us – me, Johnny, Scott, holy con-man Moloci and his sidekick J.P. with cig behind ear walking back down Elkhart like a roving youth gang towards my house. Here’s how the mob of crazy kids converged onto our driveway.

Just five ‘til Casper and the Ohioans got wind of it. Reverently, Darrell and Dan

would kneel - fans of Sparkey’s world champion Big Red Machine bowing

their heads to our ragamuffin hero. Instead they're saying, “We got Pete Rose at third.

Who do you guys have?”

“It don’t matter,” says I.

“We have Dave Concepcion at shortstop, you guys have…what’s his name? Tom

Veryzer. That aint nothin’,” bursting out into a young Midwestern laugh, which is so

devil-may-care American in tone.

In my World Series In Heaven, Mark Fidrych is on the mound, bewildering

batters and inducing groundballs to Tom Veryzer at short, and Aurelio Rodriguez,

Gold-Glover with a thunderbolt for an arm at third, and striking out the

great Pete Rose with an alchemic slider…the baseball following his specific

instructions to stay low, stay low, stay low… It won’t matter how many Hall of

Famers you have, and how many jailbirds populate our outfield. I’ll take Bruce

Kimm over Johnny Bench in Heaven, and only in Heaven, any day, any time...

And I’m intoxicated by the thrill of unveiling the Fidrych card and the growing celebrity of my little brother who struck gold. It was on this day that Pete began to carry that card - The Holy Grail - on him at all times, either in shirt pocket or back pants pocket or under pillow all summer long causing the gleam to fade sooner than it rightly should have, the edges dull, but still priceless in shoebox today.

Everyone wondered what it would look like. They couldn’t wait to see this photo that had been locked in our conscience all winter long to be imprinted in our minds till we’re gray old men thinking happy thoughts on the operating table.

We came up to our street-block tossing a baseball around, jumping playfully up and down with bats on shoulders, old Mr. Gaston yelled out from his driveway, “What’s going on here, where are all you kids heading?”

“To Dino’s, his brother got the Fidrych card!” in almost unison.

“That’s right,” I proudly say, smiling wider than I ever had, soaking the sunshine all in. Then silence until Mr. Gaston awoke from his near frozen state of open-eyed earthly amazement by saying, “Come on Mrs. Gaston lets go and see Jesus,” and she shushes him away (why d’all the crazy old men get shushed in this book?).

“Go on,” she says, disappearing once again into her Reader’s Digest. Mr. Gaston, old jokester, crazier than last year, he was in his prime right about now too - his wits, motions, vivacious sweeps never startling, instead he’d herald in a new summer down that East Side street of thick oak trees and children playing, strolling past us down his sidewalk path the same way a family member whom you know truly loves you would. Deep down you know that you’re safer than you’ll ever be. Our grand marshal of the Fidrych Parade leads us home to my driveway. I enter our house through the side door with everyone waiting outside to find Pete sitting on Mom’s lap with soft big eyes, quiet, Mom pushing his bangs away with a youthfully elegant hand - long smooth like Jackie O. - unraveling the mystery of boyhood summer.

“Pete, some of the guys want to see the Fidrych card.”

“It’s mine,” he says suddenly terrified that I would hand it over to the mob outside.

“No, no, it’s o.k., everyone just wants to see it.”

Pete looks up to Mom, she flashes her loving smile, instilling so much confidence in us all; no mob on earth could possibly scare him now. He goes to his room, leaving Mom alone in chair watching her youngest take his first tiny steps away. Pete reappears, holding in his hand by the edges, the golden card, its untouched surface still gleaming that brand new shine. He looks down at it with gentle illumination and glee. Pete lifts his head confidently towards me then Mom. Everything would be fine.

Looking out at all the neighborhood faces, he never saw trouble, only the dirty ragamuffin skyline of bats on shoulders with well broken in mitts hanging on the ends; someone bouncing a rubber ball between the Schwinn Scrambler bicycles lined up the drive with mysterious number plates tied to the handlebars; Cesar next door barking away; Connie at the far end leaning over everyone with one eye shut to the sun. All they wanted was a peek. Mr. Gaston leans in as Pete slowly lifts up the card over his head from behind the screen door with both hands.

The neighborhood boys gawked in wonder at the Fidrych card with open-mouthed amazement and envy. Then a moment of silence before a sudden mad rush down the drive and a bee-line back to Kresge’s store then Angelo’s, right next door on Kelly Road, to buy up as many baseball card packs as they could.

“Your brother got lucky, Dino!” screamed Moloci, “Hey, maybe I can talk to him, everyone has a price, what’s yours kid?”

“No price Moloci,” interjected Johnny, “we’re not selling.”

“Hey, punk, I don’t think I was talking to you!”

“Well, it’s true Paul, we’re not selling,” I calmly say.

“O.K., but if you think he’ll change his mind, just let me know,” Moloci responded as he hopped back on his Schwynn and off he rode towards Kelly Road with the rest of the hopefuls, vying for that sought after pearl.

I head back in the house to see Pete sitting behind his little desk working on his homework with Mom. “You shouldn’t bring all those kids around. Your brother gets scared easily,” Mom said while looking down at Pete with a thoughtful tilt of the head.

“I’m sorry Mom, I couldn’t help it, they all wanted to see.”

“I can’t believe a baseball player can mean so much to you kids.”

And that’s what my mom couldn’t understand. Mark Fidrych wasn’t just any ballplayer, and his card wasn’t just any card. He was the one who stirred our imaginations, and whom we were certain would lead the Tigers to their first pennant since ’68, and beat those Cincinnati Reds – revenge due to them for bombing him in the ’76 All-Star game. He was our own cosmic boy wonder. So, you could imagine our initial feeling earlier that spring when my father walked in the kitchen after work, worn down, solemn, holding the handle of his born poor lunch box with the day’s newspaper under his arm. He sat down for dinner, looked over to me and Pete sitting at our little table and told us that The Bird injured himself during spring training, shagging fly balls in the outfield. He twisted his knee, forever ruining the flow and rhythm of his perfect follow-thru, and just like that, during one sunny Lakeland day in Florida, our magic, his magic was gone. And then, upon his return came every pitcher’s nightmare –

his arm went deadd in Baltimore. It would never be the same for Mark “The Bird” Fidrych. At 22, his major league career was more than half-way over. We always believed he’d come back.

I was far too young to comprehend any of it. We all were. After dinner I went to my bedroom and glanced at the back of Nolan Ryan’s baseball card. I imagined what The Bird’s stats would look like in ten, fifteen years. How many All-Star games would he appear in? How many Cy Young awards? How many World Series rings?

At that moment, Pete stepped into our shared room with the Fidrych card, safe in his back pocket. “Where you goin’?” I ask.

“To play catch with Dad. C’mon.”

After that incredible 1976 season (19 wins, 9 loses, 2.34 ERA, lowest in baseball) he only won 10 more games in his Major League career. The next couple of seasons would mark his steady decline into obscurity, as if old age was already setting in. Mark Fidrych was rapidly and inexplicably fading away from us all. But why? Every time he came back to pitch we hoped for a glimpse of what he used to be. It never came, and into Detroit folklore he went.

Imagine walking the streets of your hometown at age nine, searching everywhere as if something near to your heart, once owned and loved by you, was now stolen. I felt angry at God, can you believe it? Nine years old, drenched in the happy sunshine on Elkhart, the aluminum siding of dreams gone by there in the all too real dusk of youth permeating through summer heat with a stumble, a dream in glee, and the now defunct comic book store (last time I drove by still searching for that “something” lost, so dissipated by the earnestness of slipping-away-time that could never be retrieved – the childhood we once had) at the corner of Kelly Road and Elkhart. How could I be so mad?

I sat on the edge of my bed with that Wilson glove in hand and thought about the summer before and every earth-loving pitch while Connie, who seemed to know The Bird’s fate all along prayed: “Let the moon shine heavenly on his darkened soul each night, m-Lord.”

I took and imitated his every move: the windup and release, the long hair, the grounds-keeping, even the ball-talking – all for the sake of my little boyhood existence and a glory that shall never fadeth away. Amen.

©2007 by Dean Ballard