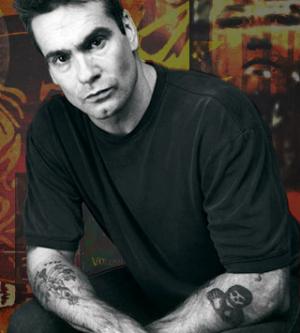

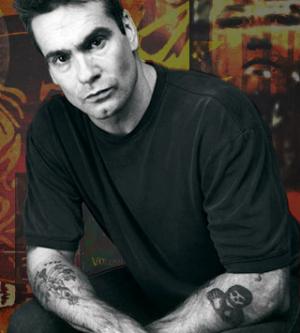

John G. Rodwan, Jr.

Recalling Henry Rollins

I saw Black Flag’s last concert, but did not realize this until twenty years after it happened.

I discovered I had been there when I read Get in the Van, Henry Rollins’s account of the

years he spent as singer for one of the most influential bands to come out of the American punk rock scene,

and it was confirmed when I saw American Hardcore, a documentary about that small,

intense subculture. I was moved to think about my punk rock past – something I had not done seriously

in many years – and to wonder how much of it had been simple teenage rebellion. The book and the movie

caused me to consider whether there could be more to it, perhaps something of lasting worth.

Rollins includes an appendix to his memoir listing the dates and cities of Black Flag performances

from when he joined the band in 1981 until the last one in the summer of 1986, which occurred in Detroit,

where I was raised and spent my time as a teenager going to shows put on by bands like the one Rollins was in,

as well as much more obscure ones. Like members of Minor Threat, the Minutemen, Circle Jerks,

Bad Brains and others now regarded as important if not especially well known, Rollins is interviewed in

American Hardcore, and in it he names the venue where what turned out to be the last Black

Flag show took place. It was the Greystone, where I saw countless bands, and where I remember seeing

Black Flag near the end of my high school years.

The book and the film sparked memories of shows at places like the Greystone, a spare, narrow hall

with a stage at one end and little else, and the Hungry Brain, a worn down former Salvation Army warehouse

in a decaying part of the city where the air smelled toxic. (The name of the venue was used elsewhere

later on, I believe, after the large, decaying building was no longer available for shows, for whatever reason.)

I was the singer in a short-lived hardcore band I started with friends. One of our (two) shows took place

in a dark bar attached to a bowling alley. I believe it was called the Falcon Lounge. I recall going

to see a friend’s band perform in some small space, and being amazed by one of the other groups

that played that night, one I hadn’t heard of before then. The Dirty Rotten Imbeciles’ riotous songs

were unbelievably fast – blasted out right to the edge of comprehensibility. The only possible

responses were to stand aside in awe of their passionate intensity or to rush into the pit at the front

of the stage and thrash about with the other riled punk rockers. I did the latter. Nights in these places,

nights like the ones when I saw Black Flag or DRI, were fueled by adrenaline and inchoate rage

(and perhaps some malt liquor).

Behaving this way, if nothing else, provided much needed release from the dreary, regimented days

spent at Catholic school, with its dress code and its dogma (which was not even subscribed to

by my parents who sent me there).

Black Flag toured and recorded relentlessly. I saw them more than once. It wasn’t until I read the book

and saw the movie that I was reasonably certain one of those times was the final performance.

I remember going to see the band after In My Head and other 1985 albums were out.

(This was a period when the band released two or three albums a year.) I liked those later Black Flag

records (and still do) but a lot of people, even among those who would go see them, did not.

I remember discussing them with people who preferred the early, pre-Henry Rollins incarnation

of the band, which had been formed in the late 1970s and was led by guitarist and song writer Greg Ginn,

who was the only constant member throughout the band’s history. There were three singers before Henry,

and drummers and bass players changed often. I saw various lineups, and I knew I’d seen them at

various places, including the Greystone. After playing the last date of their scheduled tour there,

the band returned to California , and later in the summer Greg called Henry to tell him he was quitting.

According his book, Henry regarded Black Flag as Greg’s band, so he knew then that it was no more

once Ginn was gone.

In Get in the Van, Rollins also lists a Detroit show date from the previous July and discusses it briefly.

I’m sure I attended that earlier show as well. He says it was at a place called Traxx, and that sounds familiar.

I remember that it was a bar and not just a hall like the Greystone, and that there was an afternoon

“all ages” show before the evening performance. I remember seeing the band both with and without

Kira Roessler on bass. She was one of the relatively few women in hardcore bands

(an at-times uncomfortable circumstance she describes in American Hardcore). She was not

with the band at the end.

The band hit Detroit in 1984 as well, and I may have gone to see them then too. I went to a lot of

shows in the early and mid-1980s; I cannot distinctly remember them all. (Paul Rachman,

the director of American Hardcore, shares this fogginess regarding the shows he saw in

Boston around the time I was going to them in Detroit. Regarding nights at the Gallery East,

he admits in the fall 2006 issue of FLM Magazine that he “saw so many shows there they

all get mixed up.”) I definitely saw Black Flag at least twice.

I was surprised that it took me two decades to discover that I was at the band’s last concert.

I started moving away from that scene not long after that. I’m sure I went to more shows after that one

before finishing high school the following year (and some in later years as well), but not like I had earlier.

And when I stopped paying attention, I really stopped paying attention. I didn’t realize the band broke up in

1986 – or certainly didn’t remember it – until reading Rollins’s book, which he first published in

1994, a dozen years before I got around to reading it.

Loose Nut, Family Man, My War, Slip It In – I had all those on vinyl, in addition to the one I already mentioned

(until they were stolen and sold by my sister’s boyfriend when I went away to college). I wouldn’t be surprised

if many of those who were aware of the band’s existence and had an opinion about their body of work would

regard Damaged as the best of the Rollins era. It was the first Black Flag record with Rollins

contributing the vocal, and it features classic expressions of rebellion, alienation and boredom like

“Rise Above,” Gimme Gimme Gimme,” and “TV Party.” I know many prefer the earlier material

with co-founder Keith Morris and the other singers (and some of the tracks on Damaged

had been recorded earlier with other vocalists). By the mid-1980s, the group was moving in directions

different than a lot of (less talented) punk bands. The music changed and lyrics, while still concerned

with anger and frustration, were less likely to be straightforward expressions of teenage angst.

Rollins quotes a New York Times article from early in the year Ginn disbanded

Black Flag that said it had been “growing with leaps and bounds…with every new record release –

growing musically, and that’s the hardest thing for a rock band to do.” According to the Times

critic, Robert Palmer, “On In My Head, Black Flag’s music is intriguingly, sometimes dazzlingly

fresh and sophisticated, but the band hasn’t had to sacrifice an iota of the raw intensity and directness

that are punk’s spiritual center.” Describing an instrumental album made without Rollins,

Palmer likens Ginn to jazz giant Ornette Coleman. He invokes Charlie Parker when praising

the records Black Flag made near the end of their run. I was starting to get into other types of

music around that time too (including that of musicians like Coleman and Parker), which may be

why I liked the later records as well as the shows I saw during that period.

Get in the Van, which is based mainly on Rollins’s journals, captures the thinking of a

young man who wants to write as he tries to develop his style. Much of it seems immature – even for one

in his early twenties – but Rollins evidently decided to include entries that convey what he felt

and believed at the time, even if he sometimes comes across as a jerk or doesn’t provide sufficient context

to know what to make of what he relates. The book is repetitive, but that makes sense given that it’s a

chronicle of incessant touring, of doing the same thing over and over. He has since issued additional

tour journals, such as Broken Summers, which recounts a tour he undertook to raise funds

for the West Memphis Three, three men convicted for a crime of which many, including Rollins, believe they

are innocent. That 2003 tour featured Rollins and original Black Flag singer Keith Morris performing

Black Flag songs, but was not a reunion and did not include Greg Ginn (who subsequently in the same year

did play a gig of the band's old songs as a fundraiser for a cat rescue operation, but that event did not

amount to a reunion).

One thing that comes up frequently in the tour log from the 1980s is violence, both among audience

members and by audience members against the band. He describes being punched, kicked, spit at,

burned with cigarettes and doused in urine. And he was not shy about striking back. Although my hometown

has an enduring reputation for violence, and I did see some at concerts, I don’t think it was as bad there

as it must have been in other places. There were some skinhead types in the area, but the Detroit area’s

population of racist punks who adopted a uniform of shaved heads, white T-shirts, combat boots and

suspenders (or “braces” as some affected to call them) was not as menacing as it was elsewhere.

American Hardcore includes footage of an altercation between Rollins and a would-be tormenter

from the crowd. When the singer starts repeatedly punching the other man’s face, Rollins looks gleeful.

I remember one show (it must have been the one in 1985) when a skinhead at the front of the stage

starting giving the singer a hard time – throwing punches, trying to wrestle away the microphone – and Henry

responded not with physical aggression but with mockery. A very sweaty man, he performed wearing

nothing other than small black gym shorts. Pulling up one side of them, he rubbed his ass cheek, then rubbed

the guy’s bald head, then rubbed his ass. The point was made. I don’t recall any fighting afterwards at that

show. It’s strange that people would pay to see bands they didn’t like in order to harass the performers.

Then again, those sorts of shows were very inexpensive. There was little to lose, whether you were there

to see live music or to start a fight. I remember seeing five bands for five bucks on many weekends

at the Hungry Brain. I doubt it cost much more to see Black Flag back then. And often when people

jumped on stage it was to sing along or simply to dive back off again into the crowd.

That sort of interaction between performer and spectator, whether friendly or otherwise, can only happen

when there is little separating them, and that was usually the case at hardcore shows in the 1980s. At a typical

concert by bands like Black Flag, there were at most a couple hundred people in attendance, many of

whom were in bands of their own. (And the formation of such groups often preceded knowledge of what to do

with any musical instruments, assuming any was ever attained.) Band members were apt to hang out

with the kids in the parking lot before shows or inside before their sets. I remember seeing Rollins before a

show – I think it was the last one – sitting in the passenger side of the van that he and his band mates traveled

in with their equipment (and often, he recounts, slept in as well). I went over to say hello. I doubt I said much

more than that and I can’t say now whether he replied or sat and silently glowered. Either is possible.

It’s clear from his book that interacting with strangers at shows was not something he relished. It was not like

we were fans who went to shows to see celebrities up on the stage. Those in the bands and those

in the audience were like peers.

American Hardcore captures what those events were like. It gets right that dual sense

of rejection and participation that were key to the punk rock milieu of the 1980s: the belief that we were

rejecting the arbitrary, pointless rules of our parents and the fools they elected to office; the feeling that

you can do something different from what others do or did and that you’re among people who see through

the nonsense around them and are going to try something different, even if its only making music unlike

the tired stuff on the radio. It illustrates the conviction that we didn’t need to just accept the way things

were and that we could come up with our own thing, and we could do it ourselves.

Of course, nothing like that, neither the bundle of emotions and perceptions

(and illusions) nor the community (for lack of a better word) that supports it can last. As several people

in the documentary explicitly state, it did not. Around 1985 or 1986, it ended. Maybe Ronald Reagan’s

reelection had something to do with it, as the filmmakers imply. Maybe the kids in the bands

and at the shows just got older and more cynical. For some reason, and probably several, the bands

broke up and people drifted away from whatever U.S. punk rock was. I know I did.

It would be easy to point out some shortcomings in American Hardcore,

but the film does enough well enough that it seems besides the point to name the bands that

are overlooked or whose influence is not sufficiently shown. Probably a lack of concert footage coupled

with the inability to record interviews (or even, quite possibly, copyright issues) could explain why,

say, the Dead Kennedys or the Misfits don’t figure prominently in the film, the way they would in an

exhaustive history of the subject. English bands like the Exploited, the Damned, the U.K. Subs, GBH,

the Subhumans and Discharge (and I saw all of them, too) resonated with hardcore kids in and out of bands

in the United States, which the focus on American bands doesn’t leave room to consider.

Still, though southern California and Washington DC (where Rollins lived before joining Black Flag

and where bands like Minor Threat and Bad Brains, which are beside Black Flag in the punk rock pantheon,

were based) are given the most attention, the movie does not ignore other areas, acknowledging bands

from the South, the Midwest, and other parts of the country. Watching the movie made me think,

“Yes, that’s what it was like then,” which tells me that the filmmakers did a fine job.

For me, reading Get in the Van, seeing American Hardcore

and reflecting on seeing Black Flag and participating in that scene was no sentimental journey.

I was not hoping to revisit my youth with a nostalgic walk down memory alley in duct-taped engineer boots.

Memories are never perfect records, and mine regarding that time are in no way wistful. In his book,

Rollins describes how unpleasant much of that scene was, and many interviewees in the documentary

mention the violence and sometimes sheer stupidity of hardcore.

There was something worthwhile happening too, and I’m grateful to have reminders of it. It wasn’t the colorful

spiked hair or painted leather jackets adorned with spikes and chains. It wasn’t even the raw aggressive

music played (usually clumsily) in drafty old warehouses, grungy bars and rented halls. It’s the idea

that if what you want is not out there, then you should make it yourself. Don’t wait for others to do it or just

accept the sort of art and society that’s out there now. Break it, and make it new. That’s what the documentary

captures. Reflecting on the relevance of those ideals and that attitude is not, I hope, just a middle-aged man

indulging in shallow nostalgia.

Hardcore did not survive the 1980s, despite the emergence of more commercial outfits that borrowed elements

of the sound and the look (the whole Seattle grunge thing never would have happened without it, for instance).

Still, there are those who held on to its do-it-yourself principles. Henry Rollins is one of them. In the summer of

2006 – almost exactly twenty years after the Black Flag was lowered for good, and soon after I’d read his book

about the band – he went on tour with the Rollins Band, a group (another with a frequently changing lineup) that

issued several records from the mid-1980s and to the early 2000s that melded elements of punk rock, jazz and

heavy metal in songs with lyrics filled with searching self-scrutiny, anger and frustration. He still performs songs,

with staggering intensity, wearing nothing but athletic shorts. He can do this because he keeps himself in

exceptionally good shape. Never smoking or drinking clearly worked for him. He is not just fit for someone

his age; his is fit period. And I know his age because the publishing company and record label he started

and still runs (2.13.61) is named for his birthday. He had to work the “As the World Burns” tour, which also

featured veteran L.A. punk rockers X, into a schedule that also includes frequent spoken word

performances around the world, an eponymous television show on the Independent Film Channel,

occasional movie roles and a weekly radio show. He started self-publishing his writing while still in

Black Flag, and has since published numerous books in addition to Get in the Van.

He continues to embody what’s worth holding onto from 1980s American hardcore. (His chronicle of the 2006

tour, A Dull Roar, was written and published before the end of the year.)

American Hardcore, the film, reached the small number of theaters where it was screened

about a month after the Rollins Band performed in New York, where I now live. (I might add that the band

performed in a much, much nicer theater than I ever saw hardcore bands playing in during the 1980s.)

The same week the film opened, the Drive-By Truckers, a band very different in many ways from the ones

examined in the movie, performed at another (quite nice) club in the city. Their joke-y

name belies their serious musicianship. With three singer/song-writer/guitar players (at the same time),

they sing about their experiences growing up in the South and coming to terms with its legacy.

Their set included a rousing version of “Let There Be Rock,” a song from the Southern Rock Opera

album about concerts seen and concerts missed. Far more than a mere catalogue of band names,

the song deals with the ways in which the bands one connects with in adolescence can mean a great deal,

then and later. Musical preferences and allegiances help define one’s identity. The attachments a person

makes mentally to a group may never disappear entirely, but they seem particularly strong and significant

when one is a teenager. At such a time in a person’s development, seeing a concert – or missing one – can

feel like a major event. “And I never saw Lynyrd Skynyrd / but I sure saw Molly Hatchet / With 38 Special and the

Johnny Van Zant Band,” DBT’s Patterson Hood sings.

I can relate to the Drive-By Trucker’s song, and the way bands can matter deeply to a boy and

contribute to the sort of man he becomes, but for me the groups are different. While I never saw Minor Threat,

I saw the Minutemen, Suicidal Tendencies, Corrosion of Conformity, the Necros, Dirty Rotten Imbeciles,

the Butthole Surfers and the Offenders, as well as local Detroit groups like Negative Approach, Heresy

and Ugly but Proud.

And I sure saw Black Flag.

©2007 by

John G. Rodwan, Jr.