J. Albin Larson

Noodling

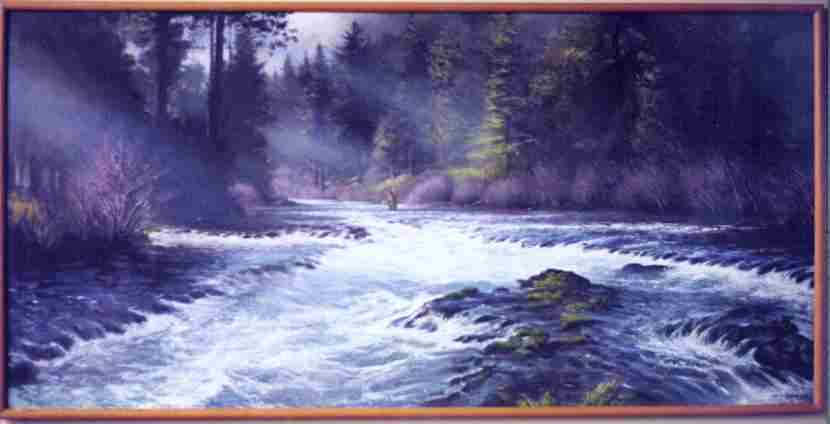

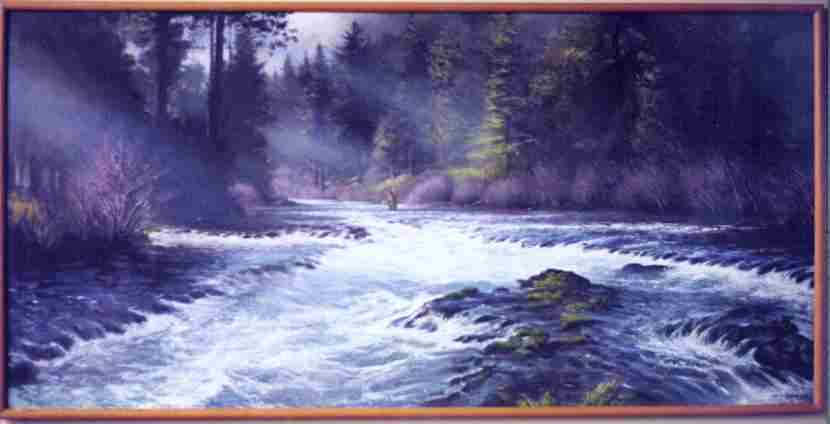

We were walking along the banks of the St. Croix River, all hard sand

and sticks and small rocks, on one of those summer days that catch you

by surprise. When one minute it's bright and gorgeous and you can

feel the sunshine on your back like it's seeping into your skin and

then, out of nowhere, clouds appear and a gust of cold air picks up

and it all-of-a-sudden gets dark.

But it was sunny, perfect, when we left the Blue Ox, where we both

worked renting paddleboats to the tourists who came around during July

and August, when it's warm enough in Minnesota to go into the water.

We got off work at the same time and I, as nonchalant and unassuming

as possible, asked Kimbo if she wanted to hang out after we both

punched out at eleven, just before the lunch rush.

It was the summer after ninth grade—before I ever

asked to borrow my parents' beige '89 Caravan or had to fill out a

Relevant Work Experience section of a job application—at the

conception of adolescence when the world consisted of my parents and

James J. Hill Middle School, the three or four two-lane roads where I

pedaled my dad's old Schwinn ten-speed, and the unfinished basements

and picket-fenced backyards I visited for video games and whiffleball.

It was a time when the outside world came to me only in Social

Studies class, before planes fell into buildings I had never seen in

person, before the world ingested the kids I grew up with and spit

them out as adults with more on their mind than high school next year

and our Mid-Western river town.

We were never really friends, but I'd been to her house and she'd

been to mine in groups for birthday parties and later stolen

cigarettes and maybe even a Zima or beer if anyone could get their

hands on one. She lived on the top of Eveline Hill, in a wooded area

where a dirt and gravel road slithered up the mountain to houses that

looked like cabins with fake log siding and massive stone fireplaces

that whispered gray smoke into the winter air like fingers reaching up

from a shallow grave in a horror movie.

Her name was Kimberly, but most everyone called her Kim. I called

her Kimbo. I was fourteen. I didn't want her to know I like-liked

her.

Until that point, our most intimate interactions were confined to a

few awkward slow dances under bawdy paper mache streamers and

low-hanging construction paper signs slung across our auditorium's

proscenium boasting things like Jan Jam and Spring Fling. There

weren't many kids at our school, only about 30 in each grade, so there

were times when Kimbo and I would dance together—my hands cautiously

grazing the area above her bony hips and her long, thin arms light and

airy on my shoulders—more than once.

I had never actually done the asking. In our town and at that age,

the girls took care of that.

Which was why I was feeling so good after work that day, walking

along the shore with Kimbo in the sun, carrying our shoes with our

socks crumpled up in them, still wearing the teal golf shirts with The

Blue Ox Resort stenciled on our chests.

I didn't have a plan per se, was just happy to be there with her,

watching the paddleboaters and fishermen strain against the

current—her skinny, pale legs sloping out of her khaki shorts, calves

flexing as her feet pushed against the sand and pebbles and sticks.

The St. Croix narrowed a half-mile or so from the Blue Ox and the

trees and brush inched gradually towards the river lapping the shore.

It became more difficult to walk barefoot, the twigs and rocks from

the woods growing more and more prevalent in the sand, and I remember

wanting to suggest we put our shoes back on, but not doing it. I

didn't want it to sound like it bothered me.

That was when the clouds slipped out from the tops of the trees and

the air got chilly. Kimbo said, We should have brought fishing poles

if we're going to be down here.

I shrugged and acted like that would've been a good idea. Then I

asked her if she really wanted to fish.

Yeah, she said. What else are we going to do?

She looked at me coyly, kind of subtle and kind of not, flashing a

half-smile I'd seen before on winter nights in the woods with

cigarettes dangling from our shivering lips, stolen beer cans freezing

in our hands. Then she said we could try and noodle for some fish.

I knew she was a good swimmer from working with her at the dock—once

I saw her dive without any hesitation whatsoever out into the river to

retrieve a paddleboat someone, me, had left untied—so I wasn't

worried

she couldn't do it. I was more worried about myself.

My dad had told me stories about going to the St. Croix, taking deep

breaths and diving down to the bottom of the river with his eyes open

and arms outstretched, squinting through the dark water and feeling

around for a hole to stick his arm in, waiting for a fish to come

along. About the noodling tournaments they used to have in

Stillwater, where the guy who pulled out the biggest catfish would win

$50 and a free All-You-Can-Eat at Dale's Fish Story Saloon.

He said that if you found the right hole, sometimes a catfish as big

as a human would clamp down on your forearm. That you had to fight

underwater and be sure to push your legs off the bottom or you might

not be able to wrestle the huge fish to the surface. My mother always

scolded him for telling those stories. She said noodling was illegal

because people died from trying it, although I had never heard that

from anyone else. Then she'd make my dad tell me I wasn't allowed to

do it and if I ever did I wouldn't be allowed near the water anymore.

Standing there along the shore with Kimbo, who looked like she wanted

to try it, I was a little nervous. Then, with that same half-smile

splashed across her face, she said, Come on, let's do it, and I

quickly agreed, shrugging my shoulders and trying to act like this

whole thing was all very boring.

I tried not to let her see I was looking as she slipped off her teal

golf shirt and khaki shorts, revealing the lines on her skinny arms

and legs where her tan from work ended and her skin became pale and

white.

I was skinny, too, and I didn't want her looking, but when I got done

taking off my shorts and shirt we both looked at each other in our

underwear and laughed. Nice farmer's tan, she said.

You, too, I said, trying to seem a little suave, a little

uninterested.

Just then, the wind blew and I saw her shiver, her arms crossed over

her small chest and white bra. It's getting cold, she said, let's get

in.

I moved forward and stuck my big toe in the river. It was cold.

Then she came up behind me and pushed and I stumbled forward until the

water was up to my knees. I could feel the pull of the current

against my hamstrings. Before she could stop laughing I dove in, my

body wrapped in cold, the St. Croix pulsing over my thin frame. She

followed and we treaded there about 20 feet from shore, our heads

hovering above the water, looking at each other and smiling, bobbing

up and down, the river water cresting up over our chins and then

dipping back down below our necks and shoulders.

So we just dive down and look for holes, right?

I guess.

Okay.

She took a long, deep breath and dunked her head under. Then her

legs came up and kicked, making a small splash and propelling her to

the bottom. I did the same.

Under the water I couldn't see much, it was so brown and dark. I

just kept pushing with my arms and legs against the current until my

eyes adjusted and I could make out Kimbo's body near the bottom. She

was slinking along like the sting-rays we saw on a field trip to the

aquarium in Minneapolis. I followed her down, my hands sinking into

the watery muck, my feet and calves splayed above my head.

We did that a couple of times, swimming to the mud on the bottom and

feeling around, then coming up for air, smiling and laughing. Kimbo

didn't take long breaks. She just came up, smiled at me and treaded

water for a second, then plunged back under. It was never enough time

for me to fully catch my breath.

About the fourth time we went down, she stayed longer than she did

the first few times, just floating along the bottom a couple of feet

away from me, the current drawing us back upriver.

I was trying hard to stay with her, to keep her in sight, when she

stopped. I ran into her softly, our bodies colliding in slow motion,

the murky brown water whirling around us. Air bubbles escaped from my

nose and up to the surface. After my eyes adjusted to the darkness

again, I saw her arm was stuck in a hole. I put my hand on her ankle

and we waited.

I could feel some pressure in my lungs and I was about to go back up

for air when Kimbo turned her head and looked at me, her eyes wide and

her long, black hair spread out in thick, sweeping strands, like it

was slowly reacting to an electric shock. I looked back at her arm

and saw the catfish's long whiskers and thick leech-like lips circled

around her elbow.

The catfish wasn't doing anything. Just letting Kimbo's arm sit in

its mouth, like it was sucking on a popsicle, getting used to the

taste of it. When I looked back into Kimbo's eyes, she must have seen

that mine were just as big as hers, that I was scared, too. I

tightened my grip on her ankle. I grabbed it with my other hand, too.

I tried to think. Tried to remember what the guys did after the

catfish bit them. But I couldn't. My head was aching, pressure

caving my forehead, and all I wanted to do was let go of her ankle and

swim like hell to the top, then go home and never say anything about

it again. I could feel the pulse in Kimbo's leg, each heartbeat

pushing blood up to her dangling feet, the water sliding over and

around them, yanking them back up towards the Blue Ox.

That's when it happened. I saw Kimbo's body jerk forward part by

part, the water convulsing around her. First her arm in the hole,

then her shoulder and head into the muck, then her stomach and waist,

her legs. She kicked, struggling against the fish, and it resonated

through my hands and arms attached to her ankle, I almost lost my

grip. I couldn't see her anymore, the dirty water riling around us,

and then I felt the muck on my forearms, my shoulders. I closed my

eyes and the mud squished over my head, in my hair, cold and thick,

covering my shoulder blades and legs and sliding over the bottom of my

feet. I held onto Kimbo's leg, my head pounding like it was filling

up, like it wouldn't hold anymore, about to explode from the inside.

The fish pulled us into the hole for I don't know how long, our

bodies taut, hanging on through the cold mud and water, until suddenly

we stopped, suspended for a moment underwater, my hands still clamped

on Kimbo's ankle, her legs limp, floating. The water swirled around

us in a whirlpool. Not knowing what to do, I kept my eyes closed,

afraid that if I opened them the fish would start again, pulling us

even further into the tunnel. Then Kimbo kicked and sent me free from

her.

It only took two kicks to get above water. I gasped for air. I

heard Kimbo gasp, too. We bobbed there for a moment, just breathing,

before I opened my eyes.

I could see a little, like we were in a cavern, weak light reflecting

from somewhere underneath the murky water, funnels of mud twirling

under my scissoring legs. It smelled like wet leaves and dirt, like

the woods on Eveline Hill after rain. I made out Kimbo's head

floating not too far from mine.

I looked up and saw the outlines of huge, thick branches curling and

twisting from the ceiling of the cavern like a tree upside down.

Kimbo grabbed one of them. I did too, its bark damp and wet, but

steady to hold. I used both hands.

You okay? Kimbo asked me, her breath steady and slowing. Her eyes

glinted from the underwater shine.

Yeah, I said. Are you?

I guess.

The water calmed a little, but still echoed, splashing against the

walls somewhere on the edges of the cavern where we couldn't see.

Is your arm okay? I said.

I think so, she said, her voice trembling a little.

I felt the muck dissipating from my chest and legs in the water. I

remember thinking I should say something comforting like I wasn't

going to let you go, but it didn't sound right. I was afraid I'd say

it and she'd laugh.

Where are we? she asked, her eyes darting around the dark of the

cavern.

I looked around but couldn't see anything, just the glint from

beneath us and Kimbo's head bobbing up and down not far from mine.

She looked at the branches stemming from the darkness above us.

Did it bite you? I asked, swinging my arm to another branch, using

them like monkeybars to get closer to her.

Catfish don't have teeth, she said.

I stopped a couple of feet away from her.

What do we do? she said.

I watched her look around for some way out, some point of exit in the

dark edges of the tunnel, her eyes frantic and her head swinging

around quickly, like the exit might have been moving and she needed to

be fast enough to catch it skirting around in the dark. I was scared,

but I didn't want her to be.

I swung over another couple of branches and held on to the same one

she did. I could feel her warm breath on my shoulder and I watched

her looking down at the water, at our legs dangling like worms on a

line, waiting for the next giant fish to come by and bite.

Hanging there in the water next to Kimbo—her dark hair soaked down

to

her head, her eyes reflecting from the water and shooting around—I

had

the overwhelming urge to put my arms around her, to squeeze her to me

for a long time. I wanted to press my lips against hers, for her to

know how much I liked her, how much I wished we weren't down in a

cavern beneath everything, how we shouldn't have gone into the river

at all, should've just gotten on our bikes and rode along the winding

gravel road on Eveline Hill and stolen some of my dad's cigarettes and

sat out in the woods against a big oak tree smoking and talking about

school or work or anything.

But she was so close I couldn't move. I just hung there gripping the

surface of the huge, slick branch with her short breaths landing on my

wet shoulder.

Do you think these are tree roots we're holding on to? she said,

shifting her grip and leaning closer to me.

I felt my shoulders tense up. Maybe, I said.

They're big, huh? I felt her bony hip brush against my stomach and

it tightened. Our bodies looked funny under the water, distorted and

paler than earlier, when we were standing in the gray light on the

shore, still dry.

Yeah, I said.

Then we were quiet for a long time. I hung there feeling Kimbo's

short breaths on my skin, her body bumping into mine, trying to think

about what was going to happen. Then about all the things I'd never

get to do. That, until then, I had been moving along like everyone

else, growing up and getting older, a constant but unnoticeable

progression towards adulthood, towards a real life in places I hadn't

been to yet, cities in other states, different rivers than the St.

Croix and woods than Eveline Hill with people who weren't from my

hometown, who had completely different histories than me but had

somehow followed a string of events that crisscrossed with mine. How

I wasn't ever going to see those places or people. How this was going

to be the end.

I remember wondering if Kimbo was thinking the same thing.

Kimbo's breathing slowed and she leaned a little closer to me, her

slight shoulder against my sternum, cold and small, shifting with the

waves in the dark. Her skin shivered in the water and I felt a knot

in my chest and back, my fingers aching on the huge, wet branch. I

looked at the side of her face, her profile silhouetted by the

reflection off the water, her hair wet and stuck together in clumps

over her ears, her short breaths glancing off my chest and armpit. I

saw her lick river water off her lips and take a breath. Then her leg

drifted over and brushed my knee, moving like a bow on a violin,

playing a slow, sad song like the ones we sat through in Music class,

when some of the kids would fall asleep or daydream, thinking about

the boys or girls sitting right in front of them, there all the time.

I'm scared, she whispered into the crook of my neck and I leaned

closer to her, my nose against her wet hair, the smell of water and

mud. I bowed my head and my nose slid down the side of hers, over the

wet hair to her ear to her cheek. Her leg moved against mine, her

shoulder lulling into my chest, her whole body shivering. She turned

slightly, eyes catching mine, wet and shiny and green like the grass

on the football field of the high school we were supposed to go to in

a few months. I felt like I had to do something. Like this was

planned, the roots of two trees growing towards each other and meeting

for a moment, considering the other and knowing innately what to do,

how to touch slightly but persist with their recalcitrant, hungry

paths underground.

A small swell of water splashed against my collarbone. I couldn't

move, my neck and shoulders paralyzed two inches from her face.

All I needed was to lean forward one more inch, but I didn't.

Kimbo blinked, turned her head, and slunk away from me, her leg from

mine, her shoulder from my chest.

The tenseness left my shoulders and I hung there slack, exhaling, my

eyes straying from her face down to a long, gray figure sliding

through the murky water beneath my feet. It looked as big as both of

us, like it could have been one of those sharks in the movies.

Kimbo saw it, too. She moved back into me, but different this time,

her shoulder and hip clanging into mine like cymbals instead of a bow

and violin.

They're catfish, she said, reassuring herself, eyes darting around

again, looking for a way out.

Then we saw another one. And another one. My body felt heavy, my

arms straining to hang on, like if I fell it wouldn't just be into a

pool of water, but off the side of a cliff. I strained my eyes

against the dark and tried to see where the cavern ended but all I saw

were the giant gray fish squirting around beneath me, like there were

hundreds of them in there with us.

Catfish can't see, she said.

Then I felt one of them skim my leg, its greasy skin grazing my

thigh. It must have touched Kimbo, too, because she jerked away from

me and swung to another branch. We held on to the branches and looked

at each other, smelling the mud, the disturbed water reaching up and

lapping our chins and cheeks.

Kimbo looked so young with her hair wet and slick against her head,

like how she used to look in kindergarten, her hair unwashed and

knotted, hanging over her face. I could see her beginning to panic,

her eyes fleeting around from me to the water to the fish swimming

blindly beneath us.

I don't want to stay here anymore, she said. We have to swim for it.

She swung her arms from branch to branch, away from me.

Where are you going? I asked.

Out.

Is that the way? I stayed put, my arms still heavy, legs still

hanging slack beneath me.

I don't know, she said, swinging farther away from me. This thing's

gotta be connected on both sides. There's little parts that run off

into the woods from the river all over. She sounded determined.

I remember thinking of a dream I had after I saw Jaws the first time.

I was swimming in a pool and "Jaws" the Shark somehow got in and ate

one of the kids that was swimming. Afterwards, there were reports

that all water was connected and the likelihood of a shark getting

into a pool was just something we'd have to deal with. I remember

telling my mother about the dream and her responding that it was

impossible. That sharks couldn't get into pools. At first, I didn't

believe her. It took me a long time to stop thinking I couldn't get

attacked by a shark in a pool.

Just find a hole and try to get to the other side, Kimbo said, still

swinging from branch to branch, the sounds of her body cutting through

the water ricocheting off the wet walls. It was getting hard for me

to see her. Then, quieter, she said, When you get out tell someone

what happened and they'll know what to do.

Fish passed beneath me and the water became more turbulent, swishing

into my mouth and over the back of my head, breaking against the edges

of the cavern, drowning out my ears. I wanted her to stop. I wanted

to go with her. I couldn't see her anymore.

Kimbo, I said, loud to make sure she heard it. She didn't say

anything back.

I was as scared then as I've ever been, but I started moving,

swinging my arms and kicking the opposite way Kimbo had gone. I had

to try. I knew she would. I stopped thinking about the swirling

water, about the catfish beneath me. When my hand felt the wet wall

on the edge of the cavern, I breathed deep and dove down with the

catfish and felt for a passage with my hands. When I found one I

kicked and pushed frantically, grating the mud with my fingers and

toes, always moving forward, pushing out towards the opening of the

tunnel, my head pulsing and my heart thrashing in my chest, blasting

blood through my limbs like fire.

In the tunnel, it felt like years passed by, like I was growing

stronger with each kick, my arms and legs bulging, dark, gnarly hairs

growing up out of my skin through the mud, memories cascading into my

brain like from a pitcher of water. The day my dad drove me to

Hastings to take my driver's test in our beige Caravan, the day I

asked a girl to Senior Prom, my first job in the city, my wedding day,

when I moved with my wife and two girls back to Stillwater to a house

on Eveline Hill. Taking my girls to the Blue Ox and swimming with

them in the shallow portion of the St. Croix, the section hemmed in by

the tough blue ropes and oblong bobbers, laughing and splashing in the

same water where somewhere out further the catfish lurked along the

bottom, the current roaring over them in recursive, violent swirls

upriver.

When I sit on my back porch on Eveline Hill now and watch the smoke

from my chimney plume up through the maze of skeletal, ancient tree

limbs into the dark winter sky, my cold, worn breath hovering in front

of me like a ghost, I think about where Kimbo must be and I picture

her far away, on the other side of the world where her tunnel spilled

out into some different, more exotic body of water than the St. Croix

and I can see her wet, long hair stuck to her head and those same tan

lines on her skinny arms and legs as she emerges from the water and

slowly steps out of the current onto shore.

©2008 by J. Albin Larson