Mary Patrice Erdmans

A live cat is better than a dead lion*

I was standing on the train platform in Sarria, bent over in one of those noisy sobbing fits, crying

like that guy on CNN whose village had been wiped out by an earthquake, his father and wife buried

in the rubble. His son was missing.

The only person who saw me crying was the wife of the man who owned the restaurant attached to

the train station. Earlier he told me that the train to Madrid left at once y media a noche,

and yet it was almost midnight and I was still standing on the platform; my drunk had worn itself into a sober

headache and I was tired of doing yoga stretches and singing The Boxer.

His wife eventually approached me and pointed out the small print on the train schedule, “ex. S.”

No Saturday night train! I had spent six hours waiting on this platform exhausted. I blamed her

unshaven husband, who by this time had moved into the back room of the bar. “But he said the train comes at

11:30,” I whined to his wife in a tone I am sure she has used with him before. He saw me waiting. He could have

told me! What makes someone cruel like that?

I cried, loudly and emotively, in public. I felt a little foolish afterwards when I saw the earthquake man’s face on

the television screen in my hotel room. It was the last image I had before I fell asleep wearing the same

stinking clothes I had worn for the past ten days.

I was walking the Camino de Santiago, a 1000-year-old, 500-mile pilgrimage route that traverses the north of Spain.

Before I left, I prepared myself by walking two hours every day for several weeks. It

rained constantly during these weeks, but still I walked, telling myself I had to get used to the misery. During these

walks, I listened to Jeremy Irons reading Lolita on tape. One day, seduced

by his voice, I sat down on a stump in the rain and listened, my mouth open, gasping into the

silent woods when Lolita tossed the apple into Humbert’s lap – ooohhh.

How confused I felt about what was right and wrong.

It rained so much in those weeks that the newscasters ran out of words to describe the deluge, the torrents, the outpouring sky-burst buckets o’ rain. And it was raining when I came back. The shaggy soggy unkempt lawns made us look like delinquent home owners; the top-heavy peonies were bent over, heads-in-the-mud dirty. Still, I loved being home. Walking my dog through drippy June roses, smelling honeysuckle close to my neck in early morning, and having a hot luxurious shower made me happy to be a well-fed hedonist born on the winning side of global capitalism.

Part of walking the Camino pilgrimage -- putting myself in situations where I walk the skin off my feet, sleep in

stuffy dorm rooms with old German men snoring, and eat stale bread and canned octopus --

is to create some physical distress in my life, contrived austerity to shape up my flabby character.

My catechism tells me suffering is good: sorrow brings us closer to God; everyone has a cross to bear.

How different would be the Greatest Story Ever Told had Jesus and his friends drank

all that good wine he made at the end of the wedding? Instead, Jesus suffers, this I know, and

the statues of the maudlin Mary caring for the bleeding Jesus stretched across her knees in the

Spanish churches tell me so.

The Camino brings together people who pay money to suffer with those for whom suffering is free. The farmers’ weathered faces do not acknowledge me, the hatless woman with long bare arms striding by in hiking boots and a backpack. Their wives, protected from the sun in cotton coats and head scarves, remain bent over weeding.

My husband asks me why I do this. I tell him I like the minimalist life, pared down to essentials with few

decisions to make. I wear the same clothes every day, and do the same thing every day --

walk, score food, wash my clothes, and recover with beer.

I walk counting my footsteps: 300 makes a kilometer; 1500 and one hour has gone by. The first morning

I walk four hours, stopping only once for ten minutes. I walk 15 miles. On flat ground with legs four feet long

and fresh energy, I lope by trios of pilgrims sauntering and chattering about the nonsense of the world.

I eat only a protein bar for breakfast and I am starving, yet proud --

so far, Mary, on so little, and all by yourself, what a strong woman you are. As if to reward me, a Spanish pilgrim named Jesus gives me a fragrant red rose he stole from someone’s yard.

At night I battle the snorers in the dorm rooms. I take sleeping pills, pray Hail Marys, pull a pillow over my head, and plead with them out loud, please just stop. Like babies crying, one sets off the others. I sleep in half-hour segments and I am eager to get out of bed at 5:30. Me and the old men snorers are the only ones awake at that time.

In the early morning, the birds are a riot of noise, stocks of them hidden in the bushes. I hardly ever see them.

Once in a while I peer into a bush or thrash around with my hiking pole and a little brown ordinary-looking bird flies

out and I think -- no, you could not have made such a big precious sound, not you, little brown bird in a bush!

One day a bird is sitting at the very edge of the bush and lets me see her. Tweet – so brilliantly loud, I am amazed in this predawn light. A shudder ruffles her feathers and I walk slowly and silently worried she will fly away but she sits steady as I pass only two feet in front of her. I look at her, my head turning as I pass, and she looks at me, her head turning as I pass.

That morning, I climb to the meseta that stretches between Burgos and Leon. The wind is stiff across the miles and miles and miles of open fields Nebraska-like in their flatness, boring in their monotone green. The hot wind burns me. I wrap my scarf over my ears and tie my hat over my scarf. The wind is so fierce I begin laughing. Every step requires extra muscle to keep me moving forward. I raise my arms and shout across the treeless fields into the violent gusts, “Give me your best shot.” Jesus passes me and waves. We put our heads down and walk into the wind.

I don’t want to stop, all I want to do is walk but my body can’t walk all day and so while walking it cries out to stop and while stopped it cries out to walk. For lunch I eat only half of my bocadillo because it takes too long to chew the thick bread. At night my legs ache – they wake me every few hours to remind me they still ache. Not my joints or ankles but my whole leg. The pain fizzles into a large mass of ouch and in the middle of the night I whimper histrionically.

I walk through the underbellies of highways and alongside roads of concrete flush with yellow irises, wild daisies, and anonymous purple flowers. My thighs are chaffed, the sole of my right foot is bruised, the tendon above my left ankle is throbbing, the second toe on my left foot has a blister, and my butt crack develops a burning rash. I am tired, aching, constipated, hungry and eventually broke because my bank put a hold on my account thinking there was suspicious activity given that ‘someone’ (me!) had withdrawn money in Madrid.

During the day I walk alone and in the evenings I talk to no one. Trying to pretend I am the only pilgrim

on the pilgrimage, I become annoyed when I hear the other pilgrims talking. Given that 90,000 people walked the

Camino that year, I am often annoyed. Walking alone my mind turns inward to my blistered soles and a knot of

lonely misery. I try to be in the moment -- watching hawks play overhead, silently eating bread and cheese,

making faces at the stone gargoyles on the churches -- but my mind won’t stay in the moment because

the moment is so damn uncomfortable.

I miss my husband, my first and only husband, but he is also a new husband and I wish him beside me on this walk which he probably would not enjoy because he is the one who taught me to seek comfort (expensive hotels, taxis, gourmet meals) rather than the twisted salvation of suffering. I start saying a rosary for him every morning. He hates that.

The mornings are the best, those first two or three hours of walking when I feel strong and the world of people is more silent. I move through Spain seemingly alone. I nod to the dogs asleep on the road, not even a nose twitch or a tail flick when I pass. On one of those mornings, after five days of walking, I come to the realization that there is no place I would rather be living than in the house that I am living and with the man I am living. And with my dog. I begin to own what I already have, to understand what I already know.

That evening, in Leon , the nuns at the Benedictine convent invite us to compline. The thin bird-like sisters in brown robes sing pure strong booming notes. I am surprised at the depth of sound and I cry into the beauty. Something stirs in my belly.

The next day I walk 25 miles in nine hours with only two short stops. The tractors and hard gravel roads through fields dotted with toilet paper from the gaggle of pilgrims continue to bore me, but in this shit I begin to fantasize. I think about my son and my eyes wet with the daydream of meeting him some day. I couldn’t take him home with me when he was born 25 years ago, but I want to see him now. I want to hug him and kiss him, but that may be asking too much. For now, I just want to see him. Okay, maybe I want to know some things. Does he have long legs? Can he be alone? Will he take risks? Is he happy, at least in the mornings, when the birds are singing and the world does not yet seem so messed up by humans?

At the end of the day my feet are on fire and I worry this might be my last day of hiking. I plunge them into a pail of cold water to reduce the swelling. The following morning I have to unlace my boots and open them as wide as possible and walk with their tongues flapping. Every day after this feels like a gift.

I meet a 14-year-old boy from the Netherlands who has been walking the Camino, with a guardian, for more

than two months. He pulls me out of my aloneness and I stop and talk with him. He rolls his own cigarettes, his

head bent over as he licks the side of the paper, he lifts his eyes up to ask me questions about myself, about

America, about life. He begs me to walk with them. Please. Please. No, I walk too fast and too long, I tell him.

That will kill you, he tells me, looking straight in my eye. Oh I want a puff of that cigarette -- I leave them.

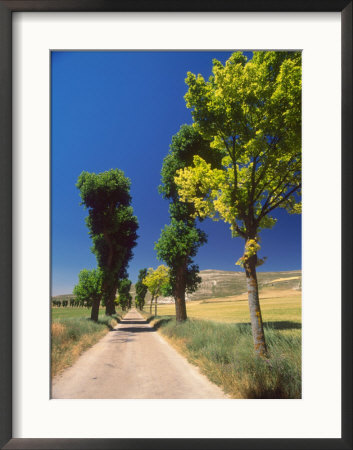

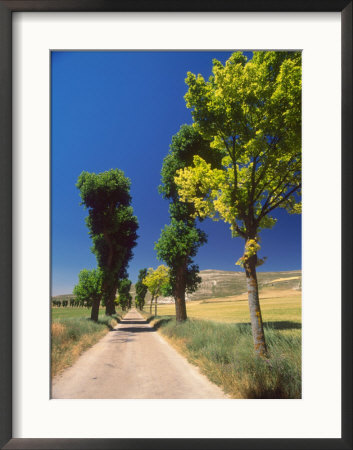

The Camino rises into the foothills. Blue skies, no breeze, hot sun, step by step I burn my arms and my legs.

Yellow bushes of flowers spread onto the path and fill in the spaces of the countryside, clumps of rabbit-eared

lavender add accents. With no trees for shade, I beat the sun by starting out with the stars still blinking, only a

crescent moon and Venus in the east. I climb 1500 feet to the Cruz. Behind me the pilgrims form a silhouette

of backpacks up the mountainside; Spaniards with bells on their bags, an American girl who talks incessantly to

anyone; two German men who talk so loudly it sounds like they are arguing; another Spaniard on a cell phone.

The mountainside scenery is spectacular, but I walk with crazed ferocity looking down at the path -- I walk

to get over and down the mountain.

I meet only a few others who walk with my intensity. One is a tall lanky Dutchman. Older. Speaks no English.

Drinks a half liter of Rioja with his midday meal and then walks another five miles in the afternoon sun wearing

heavy pants and a long-sleeve shirt; he looks rather unkempt for a Nord. He arrives into town before me. The

other is a stocky Napoleonic Spaniard -- we spend the day trading places as we hustle up and then

run down a mountain. He doesn’t keep pace the next day; it’s just me and the Nord.

In Ponferrada, after olives, chorizo and wine for dinner, I attend the pilgrim’s mass. Three

young dark-haired priests, who are also walking the Camino, each read aloud the parable of the

Good Samaritan; in three languages they tell us to love thy enemy -- I look over at the talkers and the snorers.

The following morning I share my strawberries with the old men awake with me in the blue dawn light. I spend the day walking through vineyards that roll out unendingly before me, fields that are here only because irrigation canals suck water from the rivers. The transformation of water into wine. And the wine is good.

The next day, a bit woozy, I climb 4250 feet to the town of O’Cebreiro. The first thing that greets me is the exhaust of a tourist bus. I find my way to the church and kneel with my pack on my back. It is quiet; no one is in

the sanctuary. I stay long enough to give thanks, cool off, and ask forgiveness for abandonment.

I then call my husband to tell him about the dead cat I saw in the road that morning, dead

in a pool of newly-spilled red-red blood, not even a fly around it yet. I buckled a cry without tears,

a belly moan of sadness. I tell him I want to quit the pilgrimage. I am hurt, I am sad, and I am lonely.

He tells me, Come home.

I follow the yellow arrows for one last hot afternoon, through the farm villages of Galicia dirty with cow dung. I walk until I have spent my last bit of flesh, muscle, and bone – my forearms are blistered, my ankles are swollen, and I have a stress fracture in my left foot. At the first bar I come to I take a seat, drink two pints of beer, and call a taxi to take me to the station.

Waiting for the train, my feet glow red, my ankles stiffen, my back aches for a massage. I am finally alone. I stretch with yoga poses, count minutes the way I counted steps, and in this sleep-deprived fogginess I write in my journal: “some cats come inside, but they are also loved if they are on the porch.”

A few weeks later, after I am home and the rain finally stops, I start looking for the son I left so long ago.

©2008 by Mary Patrice Erdmans