Usha Alexander

Forbidden City

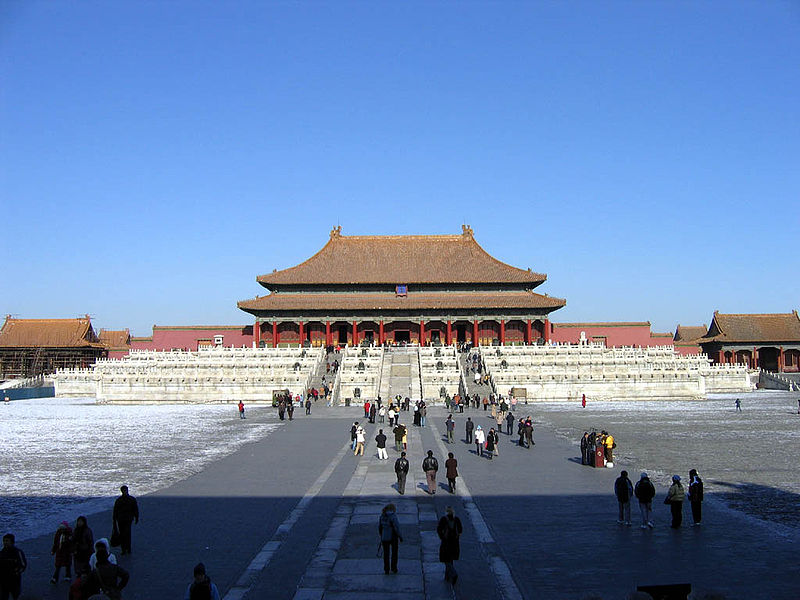

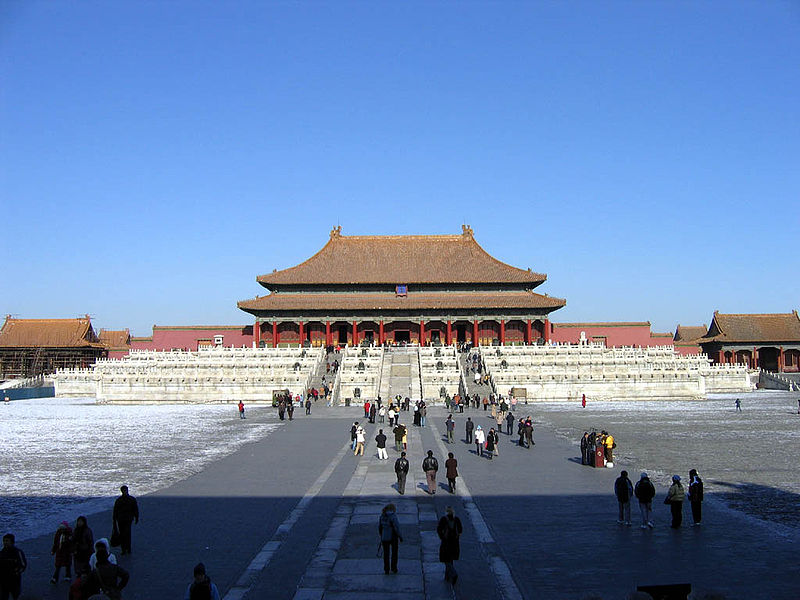

In Beijing, I spent a whole afternoon walking within the Forbidden City. Surrounded by moat and high walls, the fabled Forbidden City earned its name by

being closed to everyone outside the Chinese royal family and their eunuchs and

maidservants. The largest surviving palace complex in the world, it was completed

in 1420 and remained the ruling seat of China from early Ming Dynasty until

the end of dynasties in 1911, when the last Empress Dowager abdicated on behalf

of her charge, the child Emperor Puyi, and China was declared a republic.

Thereafter, only the inner courtyards were reserved for the young Emperor and the continuation of his sequestered, privileged life, while the doors to the outer palace were thrown open to the public. Any peasant could now enter and gawk at the home of his former lords. But as a symbol of the imperial, feudal system, even this arrangement couldn't last and in 1924 the young Puyi was evicted; his childhood home became the Palace Museum, an epic domain of cavernous halls, gilded thrones, yawning courtyards, and half a millennium's worth of accumulated rich kitsch.

At 720,000 square meters, the sheer size of the palace complex and the beauty of its finest jades and ceramics are awe inspiring, even while its decadence and intellectual blandness raise the hackles. During its heyday, some 6,000 people occupied its nearly one-thousand buildings and over 8,000 rooms, a village unto itself. In spaces with such poetic names as Hall of Supreme Harmony, Hall of Preserving Harmony, Hall of Character Cultivation, Hall of Earthly Peace, and the Gate of Moral Standards, its inhabitants plotted martial campaigns and undertook power grabs, treachery, and murder—we are given to believe, without irony. Virtually isolated from the world of ordinary folk, the anguished grievances, frustrations, and desires of crippled concubines and their castrated manservants, virgin maidservants, and ignoble nobles with too much wealth and power, too little learning or self-knowledge, must have engendered an interpersonal and political dynamic that played out like tragedian theater in a village of the damned.

The Chinese dynastic system didn't follow the rule of primogeniture; that is, the ruling emperor could choose any one of his sons to succeed him, even a son not from one of his wives but from one of his multitudinous concubines. One conceivable benefit of this practice is that it allows the possibility for a succession of rulers best suited to serve their subjects (if such a goal were valued) or to hold whatever traits might be considered ideal. To protect his boys from murderous plots, the emperor kept his successor's name sealed in a secret box until his death.

This, however, introduced its own set of complications. It begins with the question of how—if you have the requisite hundreds of concubines, any one of whom might come into power by virtue of being the mother of the next emperor—how do you make sure that none of them have sons by any other man? Answer: Cripple the women's feet so they cannot walk unassisted, and then circumscribe their world, allowing them contact only with other women and castrated men. A perfect solution, no?

Thousands of boys were purchased from their poor parents and then raised in the palace, fashioned into what they were required to be. Some grown men also paid high prices to undergo voluntary castration performed by licensed "knifers," in the hopes of gaining access to imperial power and wealth (self-castration was declared illegal).

As boys became eunuchs, girls were also sold into the service of the palace as maidservants, where both boys and girls gained the benefit of being lifted from poverty to a life of relative opulence. Though the maidservants were not physically maimed like eunuchs or concubines, they were forever forbidden from marrying—unless they somehow caught the eye of the emperor and became yet another of his consorts. But if such a lucky maidservant then bore a son who became a child emperor, she would find herself exalted to the position of empress dowager, equal in power to an emperor.

Add to this the fact that sons had to leave the palace at puberty and daughters at marriage, and an unnatural world is created within the palace, peopled primarily by women and their attendant eunuchs, rife with rivalries, alliances, treacheries, and intrigues. Plots between eunuchs and consorts strongly influenced who gained the throne and what kind of boy or man he would be when he got there: what he believed about the world, his allies, and his enemies (real or imagined); how easily manipulated by his benefactors; how aware and informed about the outside world (or not); how wise and just. But raised in this environment of intrigue, where life was minutely ordered by copiously elaborated superstitions, magical rites, and the hoary rules of imperial hierarchy, little incentive or example existed to develop the mind or examine oneself or one's received wisdoms.

And so as I wandered the broad avenues of the Forbidden City, peered through its darkened halls at the grand furniture and the material excesses of the imperial marriage trousseau, studied with wonder the implements of the emperor's seasonal ritual animal sacrifices, or admired the garden design and finely crafted jade bonsai trees, I could not escape the cloying sense of this palace as a cauldron of anguish and corruption, an inward-focused place where the most Machiavellian and petty characters would have gained the advantages of power. A bubble of privilege and vulgar ambitions, disconnected from the ordinary lives of the populace, morally adrift, it finally burst.

©2009 by Usha Alexander