Robert Stinson

Drowning in the Sun

When I see a rabbit

crushed by a moving van

I have dreams of maniac computers

miscalculating serious items

pertinent to our lives

--Jim Carroll, Living at the Movies

A rite of passage for many teenage boys is reading No One Here Gets Out

Alive, the story of The Doors, and more specifically Jim Morrison, singer, songwriter and

poet. It is a great story, but one of the flaws is (I know this might offend some people, but at

the same time those offended are not likely to be reading this. They are more likely

listening to classic rock while planning their next snowmobile trip, downing some ice

cold “brewskis” and ogling some girl that would not give them the time of day unless

they themselves were anesthetized). Jim Morrison was not a poet -- he wrote some cool

songs, and then he wrote some self-indulgent masturbatory gibberish that does not even

make sense when you read it while stoned. Most teenage boys miss out on the other Jim;

the poet Jim Carroll who thought it might be a good idea to start a rock band. This is the

reverse of the now generally accepted concept of a rock star becoming a “poet”. I truly

believe the release of Poetry Books has supplanted the Live Album as a way to recycle B-sides and rarities (You know who they are, so we won’t bother to name names here,

except Sir Paul McCartney who writes solid, stainless-steel pop songs ala Burt Bacharach,

but as poetry it falls somewhere just above Leonard Nimoy).

Jim Carroll first gained prominence, albeit underground, with the publication of

Basketball Diaries, when he was a mere sixteen years old. It is a revered (and justifiably so)

collection of poems that brought immediate comparisons to the 19th Century mercurial

prodigy Arthur Rimbaud. Carroll brings a vision that is both piercing and

poisonous. Beautiful and sexy and tragic and hip, he was a teenage junkie who

remembers what it feels like to have your head loll to your chest and watch your friend

OD like it was some sort of slow-motion black and white film directed by Dali. He

knows the kinetic feeling of being so stoned and cold and hungry and lonely and brave

and invincible, and he makes you know it too. He has lived in the place where nothing is

true and everything is permitted, and if you have never been there he brings you there, and

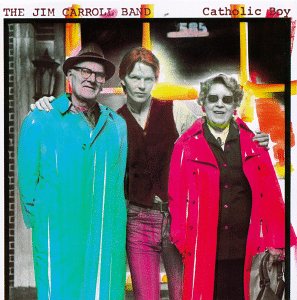

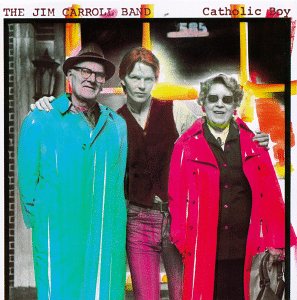

if you have been there you will recognize the smells. He brings that same vision and

tenacity and beauty to his debut album, Catholic Boy. It actually has a kind of Catholic

sensibility and visceral/sexual tension and energy, that same kind of energy that is coiled

up inside James Dean in Rebel Without a Cause, that same sense of sexual confidence that

exudes from a young Marlon Brando in The Wild Ones. At the same time, Carroll

borrows cool indifference from Lou Reed, tosses out arrogance that is reminiscent of

Dylan (think Dylan from Highway 61 or Blonde on Blonde). The sound is guitar-heavy

and post-punk, lyrics taking the forefront, and often times almost read and not sung. When

he (talks) sings it is a dystopian Springsteen, at times elegiac but never wallowing in self-pity, and in some moments rather celebratory.

It is always exciting to be the first one on your block to hear something new

like The White Stripes, Spoon, or the Datsuns. I was in London and saw the Datsuns

before they made a splash here. Going back even further, a friend in Florida gave me a

cassette tape that he had made of Nirvana months before Nevermind exploded. Re-discovering old albums can have the same type of feeling. London Calling was in my CD

player for approximately three months straight, the sounds and the furies as fresh and

exciting as the first time the plastic wrap was ripped off the cardboard sleeve and the

vinyl lovingly palmed and gently wiped clean before playing. I have moved countless

number of times in my life, sometimes by choice, sometimes by necessity, and sometimes

in the dead of night with someone after me. I have lost, sold, traded, or left behind family

heirlooms, legal documents, clothes, furniture, pets, and even friends, but I have always

managed to save my vinyl, including a number of 45’s and 78’s I ripped off from my

mom (she knows that I have them now).

Somehow the idea that music should not or could not be a part of life does not

ever drop into my stream of consciousness -- music is more than religion, an integral cog

that turns the wheels around in the machine that is the brain. Music is poetry and poetry

has musical qualities with its rhythm and meter and cadence and images that rock and

roll. Rimbaud most certainly would have started a band -- he would have been a punk

rocker, thumbing his nose at the establishment. Imagine The Drunken Boat or Ordinary

Nocturne with crisp guitar licks and haunting melodies, and you'll have an idea of the

engine that drives the Jim Carroll Band. Yes, Rimbaud’s band would probably look a lot

closer to Jim Carroll’s vision than the Doors. Carroll understands the implications and

effect that words and music can have on the brain, the body, and the soul. Like

Rimbaud, who built on what preceded him, Carroll builds on the foundation set by Patti

Smith, Velvet Underground, and Television. Morrison ripped off from the Blues, cut and

paste teen angst/sex/death fantasies, and then had the good fortune to die young at the

height of a great pop career. (Don’t get me wrong, I like the Doors and have many of

their albums, their best being their self-titled debut, a classic in its own right. Morrison

had a great presence, and he sure had the sex/drugs and rock-n-roll lifestyle down, but I

have to draw the line at "poet". We can have the Bob Dylan as poet debate another time).

So, when all the drugs that need doing have been done, and all the friendless

and unfriendly and the dead and the dying have been accounted for, what is left but the

music? Catholic Boy, ultimately, is what the eighties were all about -- and where will I be

when the straight folks are at their reunions reliving their bad hair, Katrina and the

Waves, Sheena Easton, acid-washed, stone-washed, distressed-denim heyday? I will be

wide awake in Minneapolis not wanting for much and wishing for a world without

gravity.

©2003 by Robert Stinson